The recent good-natured prosody war between

’s “Why Use Meter in Poetry?” and ’s “Why Meter Is Not Essential to Poetry” has given me occasion to put out the following piece which I have been meaning to do.This piece is not meant as a direct response to either of them, though naturally it stakes a claim on some salient issues.

I am quite sympathetic to the main thrusts of both their arguments.

This article assumes that the reader has a basic understanding of prosody, and that he understands what is meant by things like iambic pentameter, scansion, meter and so forth.

If he does not possess this knowledge I would heartily suggest the book Versification: A Short Introduction by James McAuley. It has the excellent virtues of both brevity and clarity.

Now to the purpose of this article. The following piece is a precursor to prosodic thinking. It is a re-examination of prosodic principles in an attempt to more helpfully orient the reader.

I will note briefly that everything stated here is more complicated than these brief notes would suggest, and can be expounded on at considerable length.

Prosody is a broad and complex subject that is not easily reduced to conclusive principles. Not to mention that it can be conceptualized in multiple different ways.

This article concerns the type of poetry which we call accentual-syllabic, which is the standard of Modern English prosody. I do not intend to make statements about verse types outside of the accentual-syllabic style.

My prosodic principals are those of the traditional graphic scansionists, the stressers and George Saintsbury. Specifically they are the principles of Sainstbury, with guidance from C. S. Lewis, with emendations from McAuley, and within the general framework of W. K. Wimsatt & Monroe Beardsley.1

Everything I present here is merely what I have found helpful in both the reading and writing of poetry. I encourage the reader to take it or leave it at his discretion.

I recognize the incompleteness of the notes below. I have not even attempted to describe what makes meter and verse good.

I also shall retain the right to change my mind. Especially in regards to the specifics of verse, I am open to change in a plethora forms.

Forms may die, but Poetry does not. I believe in the immortality of the Poetic Experience. The poet works with the forms which are at hand.

Because of my belief in that immortal poetic experience, if you told that me that the revivification of poetry required that I would have to burn up every scrap of literary poetry from the past 600 years, I’d say “Where’s the match?”

A few other materials should the reader be interested:

If the reader wishes he can read “Part V: The Practice of Poetry” of my essay “Poetry and Posterity.” It contains many of my thoughts on Form in general.

Also, I would like to recommend this article by

“Poetry’s Return to Form”. Setting aside the fact that my own writing is featured in it, the article is very good. It contains many stimulating thoughts from multiple sources, and not the least from Mr. Collen himself.Might I quote from the article?

[T]he real villain in Hoffmann’s story is the poets themselves, who have settled for a mere expression of personal feelings and not been willing to grasp the tradition of poetry, one which has tasked poets with tackling the great ideas throughout the ages. “Mere form is not very constructive,” he says; “it’s only appearance—façade. The conservative seems to think that skeleton needs no heart, that a vein needs no blood.” For Hoffmann, a rejection of free verse and a return to formal and structured poetry is still only a means to an end. (Italics added)

Mr. Collen quite rightly ascertained what I have been going on about. For me, Form is a means to an end. I only add this to explain much of my ostensibly strange attitude towards Form—of my willingness to both defend it and abandon it.

CAUTION: PROSODIC TERMS HAVE NEVER BEEN STANDARDIZED, WE HAVE BEEN USING THE SAME WORDS TO MEAN DIFFERENT THINGS AND DIFFERENT WORDS TO MEAN THE SAME THINGS FOR HUNDREDS OF YEARS. READ AT YOUR OWN RISK.

Laugh and Lie Down

Y’ave laught enough (sweet), vary now your Text;

And laugh no more; or laugh, and lie down next.

-Robert HerrickApproaching Verse

The Poetic Score

A poem on the page is like a music score—a piece of sheet music. It is instructions on how to recite the poem. The music is the verse and the instrument is the mouth.

It is my opinion that a poem qua poem is more properly the event of speaking it than the marks on the page. A poem resides in the tongue more surely than on the paper.

An Uncertain Question

Questions of scansion are not definitive. There are not, properly speaking, “correct” scansions. Scansions are useful abstractions which allow us to discuss the mechanics of verse. They are meant to assist us in describing and making verse. They are tools not laws.

Language Atop Language

Verse is a language applied on top of language. Or perhaps more accurately stated, it is language which is further organized according to special principles. In this case, principles of rhythmic sound.

The Shoreline and the Waves

When we first approach a poem, we are contending with two contrary metrical aspects: Meter and Word Stress. Any reading of a poem is an attempt to marry and create a union of these two things.

The Meter is the pre-established stress pattern such as iambic, anapestic or trochaic. Word Stress is the natural stress of the words as they are normally spoken.

The Meter is the shoreline. It is a set boundary of expectation. The Word Stress is the waves. They wash over the expected boundary with a reasonable regularity and similarity, nevertheless each wave is a unique event.

Actors and Minstrels.

There are two main ways to metrically read a poem. Either the reader cleaves more closely to the Meter or to the Word Stress.

This divide appears during the reading of poems when the reader has to make decisions on where to place the accent. A reader which assigns the accents based upon the established Metrical pattern is a Minstrel. A reader which follows the natural stresses is an Actor.

This is important to bear in mind because it can radically change how we experience poems thus greatly changing our scansions and metrical evaluations. A Minstrel will read five stresses in the pentameter where an Actor may happen to read three. Conversely, a Minstrel may hold to the meter where he ought not and wrench an accent.

Meter in Hand

A reader has to approach a poem with a meter in mind or else risk being thrown into chaos. He needs a few metrically interpretive lenses through which to read the poem. A pre-established pattern grants the reader an internal expectation. The idea here is that reader, after reading thousands of lines of decasyllabics, will internalize the meter and feel the deviations from it.

Expectations

Verse is not a scientific question. Yes, there are general principles, but we cannot achieve a high degree of certainty on these matters. These are indeterminate materials. We ought to be humble in our exploration of prosodic questions. We do not even quite know what “stress” is. (Is it loudness, length, pitch, quantity, etc?)

We are dealing with an unruly subject which does possess clean divisions. Here are our options: We can say that rationalizing verse is impossible, return it to pure intuition and say nothing; Or we can approach the subject gingerly and simply do our best to organize, clarify and justify our judgments.

There are of course more options, but those are the two which are the most sensible to me.

General Principles

Both Sides of the Street

Prosody is both prescriptive and descriptive. Every statement made in describing verse also prescribes how it should be written. I do not believe there is a way around this.

More properly speaking Versification is the prescriptive study of verse and Prosody is the descriptive study of verse. Despite this difference, effectively speaking, every prosodic statement is going to affect both the making and reading of poetry.

I have found that the English Foot System is both insufficiently prescriptive and insufficiently descriptive, which is the very reason it is suitable for general use.

Traditional English metrics are flexible enough for failure. Do scansionists think they’ll find the perfect metrical formula? The perfect system of meter would allow all good possibilities and deny all bad possibilities, but that is impossible.

Traditional metrical language will fail to account for good verse and fail to prevent bad verse, but at the end of the day, its flexibility of use on both sides of poetry makes it a fitting choice.

Discrete and Unique Lines

Every line is totally unique. No two lines will ever scan the same unless we achieve a sufficient enough level of abstraction to make them. The method posited in these notes, I believe, achieves enough abstraction to make scansion helpful to the poet and the reader.

Inadequacies and Sweet Little Lies

Scansion does not capture what makes verse good. At its most useful it is merely an aid for the composition of good poetry. It gives us a rationale for a line—a manner in which we can speak about it that expresses what we have already intuited about it.

The frequent refrain of many is that scansion flattens verse and that scansionists force verse into their theories. This is true. If you are not going to abstract a line of verse, then you are going to simply describe it. The level of description that the scansionist engages in is arbitrary. As in, when does one stop describing the line? Which features are salient?

For instance, the difference between using a binary level of stress (accented and unaccented) is not fundamentally different than using four levels of stress. The deciding factor is convenience, usefulness and preferred level of accuracy.

Again and again in prosody, I believe you will find that it is rife with gentlemen’s agreements over useful fictions.

When You Have the Answers I Change the Questions

The laws of Prosody cannot be fixed because time changes language. Poets change prosody as they write. The main creator of prosody is the Good Poem. Poems themselves change what is acceptable prosody.

The Norm

Aside from establishing metrical forms which are effective and pleasing, the purpose of prosody is to establish the norm of a shared metrical language.

Aesthetically speaking, the point of meter is to establish a norm. The point of writing metrical verse is to deviate from the norm. Metrical rules are made so that they might be bent. That is the whole point. Establishing then deviating then returning to the norm is a pleasurable experience.

The Primacy of the Poet’s Ear

At no point ought Prosody be using the Poet. The Poet ought to use Prosody. The final authority on all prosodic matters lies within the ear. Poems are not judged by metrical systems or prosodic laws, but by the human ear.

Prosody ultimately begins and ends in the ear.

Specifics of Verse

The Line

The line is the essential metrical unit of poetry. It is true that poems are made of syllables, but they are composed of lines. The syllable and the foot are too atomic of a unit to provide proper and useful scansion.

We are not scanning feet or syllables. We are scanning lines.

The Foot

The foot is the fundamental metrical unit of the line. As before, lines are made of feet, but they are composed of words. After composition we metrically divide lines into feet.

Just as no one consciously speaks in grammatical units like subject-verb-object, no one quite consciously composes poems in feet. As I have said, verse is a language applied to language.

Many silly things have been said about feet. There is no reason to dispose of them. They are simple and useful. And are near about the only thing which is universally known about verse. When you talk about feet, people know what you mean.

The Metrical Handshake

The first line or lines of a poem can act as a metrical handshake to the reader. They set a metrical or otherwise rhythmic expectation for the poem. They present a standard which “sets the stage” for the rest of the poem. Returning to the sheet music metaphor, these handshake lines are akin to time signatures.

It is not necessary that the handshake appears in the initial lines. They can appear anywhere, and can come in multiple forms.

The Guiding Hand

Extending the previous note, a good poem will teach the reader how to read it. If the reader pays sufficient attention, he will find the sign posts on how to recite the verse.

Simplicity or complexity of rhythm is not a mark of superiority either way. If the reader can catch how the poem is to be read in a reasonable number of reads, I think this marks a poem as a metrical success.

Like in music how a complex time signature does not necessarily make better music as compared to simple time signatures, nor vice versa.

The Separation of Stress and Accent

Among the prosodic principles I find most helpful is the difference between stress and accent. Stress is (theoretically) an infinite value and accent is a binary value. Stress can be measured on a spectrum, while accent can either be on or off.

The Principle of Relative Stress

The separation of accent and stress presupposes the principle of relative stress.

An iamb is composed of two syllables. To say that it is composed of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable is not quite accurate because a syllable with literally no stress would not be spoken. All syllables have some amount of stress in order to be audible.

Therefore an iamb is determined by relative stress. An iamb is a set of two syllables in which the second syllable has more stress. A trochee is a set of syllables in which the first has more stress. An anapest has the most stress on the third syllable. And so on and so forth for as many feet as the reader wishes to admit.

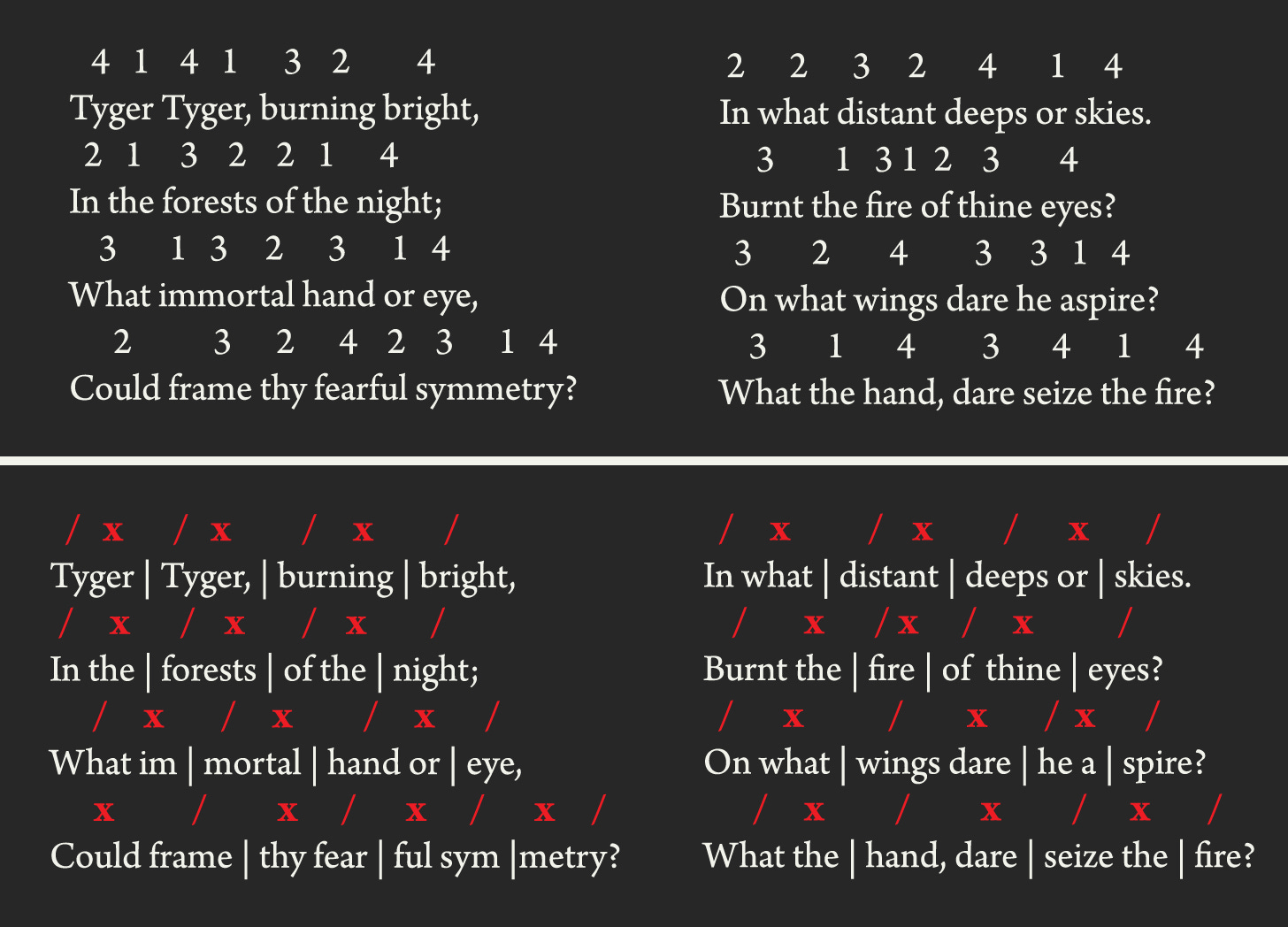

(Please have a look at the scansion of “The Tyger” above to see these principles in action.)

The Elimination of Feet

Consequentially, relative stress will practically eliminate both spondees and pyrrhics. Also it will consolidate all feet into the two and three syllable variety. Practically speaking, relative stress employs five feet: Iamb, Trochee, Anapest, Dactyl and Amphibrach.

Feet which contain four or more syllables become a difficulty if they have more than one accent.

Substitution

It seems to me that the most vital metrical mechanic of English prosody is Substitution, also known as Equivalence.

Personally I am reluctant to place most any restraints of substitution and I very much enjoy its liberal use.

Ghost Feet

The pyrrhic followed by a spondee is a frequent feature of verse. This is a fact. However relative stress will scan them as iambs or trochees as the case may be. I have taken to calling these types of situations Ghost Feet. Or otherwise using the phrase “pyrrhic effect” or whatever the case may be.

All the Tools in the Toolbox

I would rather have access to every prosodic term than not. Therefore if I find recourse to use a Choriamb, I’m going to use it.

There are cretic poems. Forcing them into dactyls or anapests because of relative stress seems foolish to me. These, and situations like these, are rarities.

Like in all prosodic matters, it seems foolhardy to change a system of metrical Norms on the account of rarities or novelties. Let them stand on their own as the weird little fellows they are.

As a final note, here at the end, I have found that with the following concepts, I am able to scan most all verse: The usual single accent bi-syllable and tri-syllable feet, the principle of relative stress, the principle of tri-syllabic substitution, catalexis (broadly considered), anacrusis, redundance, irregular lines, imperfect feet and hypermetrical syllables.

Also, with use of all these concepts, I find accentual-syllabic verse to be a very flexible, expressive and comprehensive medium.

The Primacy of Intuition

Despite our inability to perfectly describe meter, surely it exists. We all can point to the finished poem and go “there it is.” Which suggests that even if we cannot rationalize it to degree which we might prefer, we nevertheless intuit meter’s existence.

The indeterminate materials of Poetry and Prosody are always going to be up for debate and subject to argument. This is because of the two doctrines of poetry:

1: The mind of the poet gains insight into reality and represents that which is not ordinarily perceived.

2: The mind of a poet creates reality into which he projects something of himself. (Note that I say reality and not Being or Existence. Reality is positioned between Man and God.)

If we reject the first, we deny that something outside of us exists. If we reject the second, we deny the existence of our Intellect.2

Special Observations

“Metre is, I think, [the poet’s] lawful wife, but I would allow him ametric rhythm too when he chooses it as a pretty and pleasing mistress, provided that she is pretty and pleasing, for , unfortunately, she has rather a tendency to be neither. But I would never allow her to turn the wife out of her place.”

-George Saintsbury

In Favor of Meter

The arguments which derive rhythmic value from the rhythms in Nature are only good enough to argue for rhythmic poetry, not necessarily metrical poetry.

Arguments for metrical poetry are much more solidly grounded in the idea of interplay between a metrical norm and the variation of stress. Which is to say, these arguments take place on the level of effect and purpose.

Accentual-syllabic meters gain in precision over more lax meters, while Free Verse gains in the luxuries of speech-feeling. This is where the battlefield lies.

It could be said that Free Verse is like painting with a brush, Accentual-syllabic verse is like cutting into wood, and Alliterative verse is like carving granite. It seems to me that this type of thinking is more helpful than merely asking which verse is best. The question is, best for what end?

The Primacy of Meter

Alternatively, here is a different line of argument we might pursue. I am taken to believing that formal versification is the primary structure of poetic order. This does not deny the existence of secondary and tertiary structures of order.

The point here is that a-metrical verse may require and presuppose metrical verse. Does a-metrical verse lose its impact with the depletion of metrical verse because the internal metrical expectation of the reader has also been depleted?

20th Century Schizoid Man

The twentieth century obliterated our standard verse. The norms are out the window.

I don’t know what to do about it. There, I said it.

The Machine’s Ear

I discard out of hand all sonic measurements by a machine. The human ear is the only recipient of a poem that matters. I don’t care how a machine hears my poem.

Across the Pond

It is important to note that all of the traditional texts on metrics were written by speakers of British English. It is my belief that because of the differences in the American English accent, American English may admit a different prosody.

An example of this is that, to my ear, purely syllabic verse reads rather smoothly in the American accent. I don’t know where this might lead, if indeed anywhere at all.

Robert Frost said that there are two meters, Strict Iambic and Loose Iambic. Even accounting for Frost’s usual mischievousness, there is a great deal of truth to it. Does that truth pertain to what we might call the American Meter?

Secrets

It is common to hear statements like “The secret to English prosody is X.” Such as “The secret to English prosody is the influence of Strong-stress and Vowel quantity lurking in the background.”

Whatever the secret may be, perhaps it ought to remain just that—a secret.

The Poetic Contract

Underlying meter and verse is a tacit agreement on how verse ought to be written. The only precondition being that a form is found that is suitable to the language itself. Beyond that, “we” make the next decisions.

It may be the case that Meter presupposes a People. Indeed it may be the case that Poetry itself presupposes a People. If this is so, it might very well encapsulate the entire mystery as to the decline of Poetry.

I have the following writings in mind: The aforementioned Versification by McAuley, The Historical Manual of English Prosody by Saintsbury, “Metre” by Lewis (it can be found in his Selected Literary Essays) and “The Concept of Meter” by Wimsatt & Beardsley. If the reader peruses this materials, he will find that I have stolen from them extensively in this article.

I’m not a philosopher. These words are surely inaccurate and insufficient. I only mean to say that a poet both “discovers” and “creates.” That seems a plain enough fact to me. These words are only a facile attempt to represent that fact.

Thank you for mentioning “substitution”. I think this is a key technique often referred to as poetic license. Many people that I have come across do not understand it, probably because they are not familiar with musical improvisation and variation.

"Does a-metrical verse lose its impact with the depletion of metrical verse because the internal metrical expectation of the reader has also been depleted?" That's a *really* interesting question, Nik. I'm aware, for example, that my appreciation of Skunk Hour by Robert Lowell (who, as I'm sure you know, started off as a strictly formalist poet) is enhanced by my comprehension of traditional meter - despite this being considered a seminal "free verse" poem.

Your "20th Century Schizoid Man" comments made me smile!

Though you say much I agree with, I'm going to offer what I hope might be constructive counters to some of your statements.

"Aesthetically speaking, the point of meter is to establish a norm. The point of writing metrical verse is to deviate from the norm. Metrical rules are made so that they might be bent. That is the whole point. Establishing then deviating then returning to the norm is a pleasurable experience."

This needs clarification, I feel. For a start, even the most metrically unvaried verse can have expressive variety through the interplay of phrase and line (enjambment), and the internal interplay of word & phrase with meter. Often, for example, when I come across a passage in Shakespeare where the lines are broken up into many short or enjambed phrases, there is very little *metrical* variation; it's not needed.

A metrical template can also be exploited to indicate emphases that would not be obvious to someone not metrically literate.

And subtle variety in movement, speed, and rhythm is inevitable even against a backdrop of unvaried beat placement and smooth end stopped lines: both subtle ripples and dramatic waves have aesthetic and expressive value, as does everything inbetween.

So I would say that you simplify and overstate your case here.

And then there's the question of what you mean by bending the metrical rules. Even in the most conservative tradition, there is a standardised range of permissible variation within iambic verse - principles which were fully and consistently established by the end of the 1500s. The vast majority of English verse since then *conforms* to these "rules". If you'd referred to "the default metrical template" as opposed to "metrical rules", your meaning would have been clear - if that is, indeed, what you meant.

"The foot is the fundamental metrical unit of the line. As before, lines are *made* of feet, but they are *composed* of words. After composition we metrically *divide* lines into feet."

Your last sentence contradicts your previous assertion. "Foot" division is indeed something that some people *apply* to metered verse for the purposes of description and analysis; what *defines* a meter, meanwhile, is the number of beats per line and their placement (if you prefer to say "accent" to " beat", that's fine!). Foot division (done successfully) is simply a *process* of marking off the beats in a simple and consistent manner; to say that "lines are *made* of feet" is a fundamental category error.

And it leads to woolly assumptions. For instance, iambic meter is almost universally described as a "rising rhythm". No. It is the words and phrases *within the line* that create rising or falling rhythms. Applying foot divisions doesn't magically make the rhythm rise!: https://qr.ae/pGeXBo

Traditional disyllabic "foot" division, which attempts to mark off each individual beat separately, has, in my opinion, limited utility.

Firstly, at a fundamental level, it can actively *obscure* beat placement. A beat can be either recoiled (a "trochee" in foot terminology) - *or* it can be pumped forward. And that's where disyllabic foot division fails. I'll explain.

When a beat is recoiled, "di-DUM-di-DUM" becomes what I call a "swing": "DUM-di-di-DUM". Which you would define as a trochee followed by an iamb: "DUM-di | di-DUM". Fair enough.

But when a beat is pumped *forward*, "di-DUM-di-DUM" becomes "di-di-DUM-DUM". The beats land on the last two syllables of this pattern. And yet you would divide it into a "pyrrhic" and a "spondee": "di-di | DUM-DUM". Which totally obscures the beat placements! And the whole *point* of foot division is to mark off the beats! **

The above illustrates a more general point: disyllabic foot division is choppy and artificial, and is quite poor at conveying what we actually *hear* when there are variations in the meter. We do not, for instance, *hear* the "trochee followed by an iamb" *as* "a trochee followed by an iamb" (except in the rare case where there's a phrasal juncture in the middle of the pattern). It doesn't appear I can share photos in comments, so I posted an example of my own approach to scansion on BlueSky (you will see that I only mark variations from the default. And no foot divisions! Only very occasionally do I find it necessary to add a foot division, to clearly demark two separate patterns): https://bsky.app/profile/8dawntreader8.bsky.social/post/3lkjlccodoc2y

** I'm going into incredibly nerdy detail here, but there is an exception: the appended pyrrhic followed by a spondee (appended pyrrhic = two light syllables at the end of a word).

As it happens, I can illustrate the difference with the opening and closing lines of the poem I've most recently memorised.

"As KINGfishers CATCH FIRE...". I hear no beat displacement here: I hear the 2nd & 3rd beats land on "...shers" & "fire".

"...the FEAtures of MEN'S FAces". To my ear, the 2nd & 3rd beats land on "men's fa...". There is no beat on "of": the 2nd beat is pumped forward.