Preface

This is a collected, revised and expanded version of five essays previously published on Substack.

I have provided a pdf of this post for easier reading. I would heartily recommend reading the pdf file instead of the Substack post due to the limitations of the Substack formatting. The pdf has much superior formatting, especially in regards to the footnotes. It is a much better experience, however the substack format is not terrible and will suffice.

I would like to thank all my readers and all those who have provided feedback on this essay. You all have my gratitude.

Introduction

Poetic Presuppositions

The following piece of writing is about Poetry, and further, about Poetry’s relation to us and to the world. Also it is about Posterity, by which I mean both our own duty to pick up the Tradition handed down to us, and our role in passing down that same Tradition. The “handing down” is not done for the sake of tradition, it is done because tradition is good. Likewise we do not pursue poetry solely for the sake of poetry, we pursue poetry because we pursue something better—the Good. It is only in this configuration that poetry is able to blossom in and of itself. The further that Poetry is divorced from Good, Truth and Being, the less it achieves any significance or meaning.

However a problem soon presents itself, if a poet describes the world as beautiful, but the world is not beautiful, it is a lie. If he shows Creation as evil, but it is not, he has misled his hearer. Lies may crumble in the course of time, though often not without causing some amount of damage. The greatest condemnation of poetry is found within this basic problem of Beauty and Truth: Poetry can speak in beautiful lies. Deceptions are very often beautiful. The Deceiver disguises himself as a messenger of light.

Allow this analogy: There are many beautiful women, this is good. There are also many beautiful women who do not love you, again this should be no issue. However, if there is a beautiful woman who says she loves you, but actually does not, what comes of this? Tell me, what shall win in the end, her beauty or her love? Which would you prefer? Is her beauty or her love of greater worth? The reader must search himself for the answer, it is not as easy of a decision as it first appears.

There is a great amount of nuance regarding the truthfulness of poetry. Man is an emotional being, and since he exists in an imperfect state, his emotions are disordered. The expression of Man’s emotional state in poetry is inveterately bound to be disordered in some respect. The question, then, is if men can represent their disordered emotion in poetry without becoming further disordered. I believe the answer is yes. Further, I believe purgation and catharsis of disordered emotion is possible. The act of achieving this aim is an art, and definition of its principles is, to put it mildly, difficult.

Putting the moral sense aside, we might ask ourselves if poetry is capable of accurately describing the truth. Is not metaphor, which poetry so very often employs, a false understanding of a thing? The problem is immense and requires great philosophical consideration. However, I have never known a great teacher to eschew the metaphor, and great philosophers throughout the ages have both used them and defended their use. Neither did Christ Himself avoid the use of the metaphor. The Gospel’s are abundant with them.

If the condemnation of Poetry is the Sublime Deception, then the redemption of Poetry is the Sublime Truth. This, of course, is contingent upon one’s conception of the Good and the Truth. This essay rests on Christian assumptions about the Good. All Goodness and Truth ultimately point to God and Jesus Christ. However, in discussing the Good, we can approach things in a way that is more acceptable to human reason1. Reasonable men believe in the Good, not all reasonable men believe in Christ. (This is not to say that belief in Christ is not reasonable.) If the Good leads to belief in the Christian Faith, all the better.

I do not believe that poetry can exist in anywhere near the same manner or stature, if it is disconnected from the Good. Can poetry justify itself solely on the terms of amusement and delight? The answer is likely yes, however this would result in a great reduction of Poetry’s stature. If someone wishes to construct a theory of Poetry that is self-sufficient and self-contained, let him try. However, it is not my problem, as I do not conceive of the world in that manner. Not only am I happy to legitimize poetry via reference to the Good, but also, to claim that Poetry receives its life-breath from the Good. And here I do not mean the Common Good, but instead the True Good, the Supreme Good, the Transcendent Good—the ultimate and final repose of man’s love.

The legitimization and source of poetry is inescapably connected to love. We might love the Good because it is beneficial to us. However, the perfection of love is the transcendence of motivation. We love the Good because we love the Good. We may end with a tautology, but sometimes tautologies are true. God created the world out of perfect love, with no selfish motivation. Indeed, therein is the house of poetry—the preoccupation with the mystery of the world and of life, where the soul is ultimately moved by perfect love.

At the Limits of Poetry

God gives man poetry as a Father gives his child toys. They are there to entertain, amuse, delight, and teach. Even though playing with a ball grants a lesson in dexterity, that fact does not hamper its enjoyment. Notwithstanding moral guidance, poetry can remain fun. Poetry is Man at Play, but it is serious play. During the course of play, we experience the world in miniature and in relative safety. A child can build a tower of blocks, and crash them without penalty of death. An architect does not have that luxury. A poem can allow us, in a manner, to experience death without dying, or experience love without loving. Poetry can be a preparatory foretaste of mature and consequential things. Poetry trains Virtue; Let’s be careful not to confuse Poetry with Virtue, but we ought to recognize the relationship. And let us recognize that just like a child’s toy, poetry is a gift—a gift of Fatherly love.

A gift ought not be abused, just as it ought not be rejected. The maker of a poem has not rejected the divine gift, however now that the inspiration has been placed in his hands, he ought not abuse the Muse. The poet has a responsibility to not be bad; Whether it be in the gracefulness of his verse, the correct ordering of emotion, the proper treatment of his subject, the maturity of his consideration, or some such other standard.

If the gift of poetry is misunderstood, a narrowing of scope and power occurs. The closer poetry veers towards Triviality the less it is judged. Counterintuitively, the less it is judged the more dangerous poetry becomes. The fact remains that poetry is a powerful art, which possesses an ability to move and influence the soul. If poetry is let loose of standards, it descends into anarchy. Poetry becoming ungoverned does not rob poetry of its powers, it only means those powers are now running wild.

It must be said that more important things lay beyond the limits of poetry. Higher powers make higher claims than the domain of poetry can muster. If a conflict arises between Truth and Poetry, Truth must be given sovereignty. Poetry is no Atlas, if it is tasked with upholding the whole of Life and Being, the unbearable weight will break poetry’s back. This is why Literature fails to succeed as a Religion. If poetry must be sacrificed on the altar of prayer, then so be it. The reader knows where my loyalties lay.

However, I believe in a more harmonious vision of incorporation. It seems to me that Poetry and Truth can exist in a fruitful relationship. As long as it is not burdened beyond its limits, poetry remains a legitimate form of knowledge and human activity. Poetry and Truth can maintain a counter-punctual relation to each other; One calls, the other answers and neither voice is silenced. If we wish, we could look to the Boethian Example, where Poetry, Philosophy and Man all seem to cooperate in a symphonious palliative, singing sweetly even through the cacophony of the unjust death.

Despite the limits of Poetry, it still retains claims of its own. Poetry can be ill-governed by higher powers. One such, is the subjugation of Poetry to Virtue, that is, an understanding of Moralism which rejects transcendence. A certain kind of moralism can tyrannize poetry. By demanding a grossly tight grasp over the activity of poetry, a moralist can destroy poetry. A moralist who never allows poetry to fail, never gives it the opportunity to succeed. A totalizing moralist only allows poetry to succeed at becoming a moral dictation, and disallows poetry to succeed as poetry. It should not be hard to see that the moralist quickly transforms into the ideologue, at which point the lovely face of poetry is transmogrified into the hideous visage of propaganda.

Poetry ought to remain poetry, and the claims of Poetry should be allowed to flourish. Perhaps the greatest of these claims is Inspiration. Lest we should grow too prideful in the power of human reason to know or to organize society, the phenomenon of Inspiration will humble us to our core. In the final analysis, Poetry remains a Gift, and indeed a gift that comes from beyond. The totalizing moralist or the Ideologue does not appreciate the transcendent necessity of poetry.

The Ideologue, or any tyrannizer of poetry, does not understand that the Muse chooses whom she wills. The capture of the Muse is the purview of Magic, not Poetry; And often when you trap the Muse, it is she who is trapping you. The insidious face of deception may reveal its hollow core of pretense, but only after the magician has surrendered over his soul as payment for ill-gotten and misunderstood gains. When you trade Love for Power, you are not truly given Power, but instead Simulation. The Magician’s power only exists within the hall of mirrors where the façade of infinity reflects unto the façade of infinity.

We do not have ultimate power over poetry; True poetry is received. Poetry claims that Man is a receptive being, a vastly important fact which reverberates through our relation to the world and Being. To conclude the point, if man is a receptive being, it implies that there is something to receive—that there is a voice from beyond which calls out. The existence of Poetry, well-understood, forcefully suggests the existence of God and further, that He is an intensely personal God.

Now, the phenomenon of Inspiration does not mean that poetry is pure Inspiration. We must also reckon with the existence of Craft. Poetry is concerned with both Craft and Inspiration. Poetry begins and ends in mystery—in inspiration—but in between is craft.

An illustration: A farmer does not grow crops, that is, he does not directly cause vegetal growth. He doesn’t grab the vines and make them grow. The growing takes care of itself and he provides the attention and care which allows the crop to come to fruition. Likewise the poet does not cause the poem. Inspiration precedes him and he attends to it, however the importance of craft is no small thing. Just as a farmer has much to do with the quality of the crop, the poet has much to do with the quality of the poem. God produces life, man’s task is to attend to the nurturing of that life.

Indeed, there is spiritual soil where the poem grows, and which we are tasked with stewarding. Maintaining the soil of poetry is the purview of the poet and critic alike. Inspiration and Craft work together to restore and preserve the health of poetry. The poetic field where you labor will fall to the Posterity’s care, upon your death. Whether it is the upkeep of art’s highest maxims, the clarity of language or the sensitivity of taste, the soil of poetry must be properly stewarded. The fruits of poetry are too precious for the fields to fall fallow.

The fruit of poetry is the transcendent moment. Our aim is that moment in time when the hearer, upon the hearing of the poem, experiences the interpenetration of the poetic constellation of beatific meaning and himself. The immediate and the transcendent intertwine to fashion a thread leading to a glimpse of eternity. In that instant, you forget you exist. With the onset of an approaching revelatory moment marked by the sway in the pit of your stomach like a tower approaching collapse, you undergo the pure fire of emotion, and the numbness of the body, and the silence of the mind, and the unsparing clarity of sight.

Despite that high aim of the transcendent moment, very few of our poems will achieve such greatness. In this vale of tears, the world is fallen and imperfect, and our poetry is no exception; And though we strive for perfection, it is of no surprise when our actions do not live up to our intentions. We can only do our best, be content and say our prayers.

Again Who with a little cannot be content, Endures an everlasting punishment. -Robert Herrick

Present Purposes

The purpose of this essay is to exercise the Moral Imagination for the purposes of developing a Moral Vision. I would like to suggest that poetry is a fitting avenue for exercising and furnishing the moral imagination. By moral imagination I mean the faculty which connects the power to rightly divide good and evil—that is, the Virtue of Prudence—with actual application in the workaday world. Applying prudence to the actual, specific challenges in our lives, whether they be personal, communal, political or otherwise, requires the exercise of the moral imagination. When I say “Poetry trains Virtue” that is what I mean. Poetry can develop the moral imagination which is then able to translate general virtuous knowledge into specific, everyday actions.

A lack of a Moral Vision in Man is a deficiency in his being, and it is necessary to possess a moral vision as his nature demands it. It is easy to talk about “creating” or “building” Moral Vision, but this is only an analogy. A Moral Vision is more properly said to be “seen” than to be “built.” The establishment of a Moral Vision is contingent on the “soundness of the eye” and like a lamp, the eye enlightens the body. Achieving the steadiness and clarity of a “sound eye” is no easy thing, and is beyond the strength of poetry. However, poetry plays no small part in the endeavor to establish and propagate a Moral Vision.

I believe that it is a moral good that a man should see and know reality correctly. Poetry is indeed preoccupied with seeing and knowing reality. As soon as poetry rises above a purely aesthetic exercise (and due to natural human curiosity, this is inevitable) poetry becomes interested in knowing things and describing things, and particularly how we, as men, feel about these things.

Despite my understanding that Poetry, in addition to other things, is a moral enterprise, the reader should understand that a moral poem does not mean a didactic poem. Moral poetry does not equate to Legalistic Poetry. The representation of evil things does not make a poem evil. One should not underestimate the nuance and complexity of this. It is very natural that men should struggle with dividing good and evil. It would be completely inhuman to expect that wrestling with Virtue and Vice should be absent from our poetry.

Now as for the content of this essay, the reader will notice a lack of the question “What is Poetry?” I will offer many descriptions of poetry throughout this essay, however I have not made an attempt at definition. My eye is trained towards a practical understanding of Poetry. The recurring theme throughout this writing is poetry’s place in the world.

Also the reader will notice a lack of specifics when it comes to “What the Posterity Should Learn.” I feel that this work has already been done by the classical educators of recent years. I do not have any pedagogy or curriculum to propose. I am much more concerned with connecting ourselves to our forerunners and the following generations to both ourselves and the Tradition. The proper poetic attitude should be that which keeps in mind both the past and the future. My hope is that the poet sees himself within this great chain of being, and that his poetry reflects this orientation.

There is a lack of specificity in this essay. This is because of my conception of poetic practice. I appreciate and love variety. I would never wish that poems become one way or operate on one singular stylistic principle. Below, I use the image of a garden surrounded by castle walls; This represents my attitude. I prefer that there would be controlled and orderly coming-and-goings, but inside, within the garden, I promote autonomy to the greatest degree possible without causing violence to its fruitfulness. To put it more plainly, the practice of criticism is not only to divide good and bad, but also to identify and ward off threats to poetic practice.

I have attempted to present several pairs of things which do not easily synthesize: Craft and Inspiration, Moral Virtue and Pleasurable Beauty, The Common Good and the Supreme Good, Purposeful Art and “Purposeless” Art. These concepts bring many difficult questions to the fore:

“If the source of true poetry is inspiration, that is, beyond craft, what is the point of craft?” “If true poetry must not be beholden to immediate concerns and or else risk degrading into propaganda, how can poetry serve a moral purpose?” “Should the Supreme Good be pursued to the point of the Common Good’s destruction?”

Each of these questions deserve much careful consideration. However, what can easily be said is that we don’t really escape the “Golden Mean.” Poetry is always in danger of “too much of one thing and not enough of the other.” Therefore we require a Moral Imagination which is ultimately moved by total love. We should love the entirety of Poetry, without leaving anything un-considered, even if considered imperfectly. The complete love of Poetry implies that we desire its perfection—that it achieves the fulfillment of its station within the Cosmic Hierarchy.

Guide to the Use of this Essay

My hope for this essay was that a unity would arise out of its disparate parts; And that considered together, it would serve as a sketched-out blueprint for the further practice of poetry. I have put forth various methods and modes of poetic talk which have included polemic, analysis, explication, symbology, history and criticism. Though I don’t believe that I have done much to synthesize these elements besides simply housing them under one roof. However, I see a synthetic vision for them all and have attempted to put it into practice.

A major concern of this essay is working on the framework for the building of a fruitful poetic environment. This is why, though much of this essay is theoretical in nature, it is pointed towards the practical. I am under no illusions about the faults of this essay. I undertook this revision2 in hopes of getting it into shape, and presenting the best and most useful version possible out of its flawed components. This essay represents a journey, from the opening polemic to the closing comparison of poems, I endeavored to make my way through our current poetic problem. It is of great importance that this essay ends on the practice of poetry, because I believe that is what is left to us to do.

In addition to the journey, there has also been wrestling; Wrestling with many difficult problems and with the uneasy state of tension that they are left in. Many things are underdeveloped, and some things—important things—have been left unsaid. I most likely emphasized some aspects of poetry too much and have not given enough attention to others. I can only hope that the usefulness of this document will outweigh its shortcomings.

Part I is a polemic and I hope that the reader will bear that in mind. I truly mean the things I say, even if at times, I let the tongue wax rhetorically tumultuous. It is merely an opening salvo in the warpath I have pursued—a dual-front theater which attends to the twin aims of stymieing the momentum of current poetry and blowing open a way forward for a traditional, reactionary and forward-thinking Moral Vision.

Part II comprises two main concerns. The first is searching for and grappling with what makes contemporary poetry tick. What is its defining characteristic? The answer I have presented is fundamentally an avoidance of death and ultimately a massive reduction in the importance of human life. The second concern is my frustration that the fight over poetry is not over poetry. The fight over poetry is a proxy for a fight over basic existential values. Arguments about contemporary poetry only serve to subvert the basic underlying issue, which is a contest over whose Moral Vision governs.

Part III is further expression of my frustration at that same subversion, which undermined previous efforts at establishing a traditional Moral Vision. The main conclusion which can be drawn out of this history of sabotage and failure is the adoption of a new attitude. Perhaps we can become wiser and less naive; Learn from past mistakes and operate in a more prudential manner.

Part IV can be simply summarized as Christ or antichrist. That is really all I endeavored to describe. It is an exercise in symbolism, and more, a poetic exploration of Poetry and the World. This ground has already been tread, particularly in Part II. However, I committed to this poetic experiment in hope of perceiving more deeply into our current problem. This part is terribly dense and I would encourage the reader to rely on the notes for clarification, as I have provided little help otherwise.

Part V is the end of the journey. However this end is but another beginning. The practice of poetry does not end where I have left it. It goes on and on. Poetically speaking, we now exist as the children of Theory—the academic poetics of the 20th century. Countless points of order have been overturned in the wake of Theory; And flatly, I believe that Theory has not been honest in its aims. Theory’s potency as a weapon is too effective to ignore. The men of the margins went to war with the men of the norm. It was no war of strength or idea, but instead a war of cunning and psychic manipulation. The men of the margins have tied quite the impressive Gordian knot. However, they may live to regret their clever skepticism, their destruction of normative values, their tearing down of old things and their bacchanalia of historical-criticism. With the enormous volume of their prideful braying, they may have awoken the enemy of their paralyzing knot—the men of the sword.

Answer Sound, sound the clarion, fill the fife! To all the sensual world proclaim, One crowded hour of glorious life Is worth an age without a name. -Sir Walter Scott

I: Circumstance Considered - A Polemic

The question3 before us is “What do we wish to pass on to our sons and daughters?” The answer, as always, is to pass on The Permanent Things. In a word, the Posterity should be taught that they are human, and that they have a nature which makes them so. From the question of human nature emerges the concomitant “Questions of the Cosmos”: “What of God?”; “What of Purpose?”; “What of Duty?” Now, the exploration—and revelation—of these questions has been put forth in many different ways. However, one of the permanent activities of mankind, which has concerned itself with these ponderings, is poetry. Poetry has played no small role in the “handing down” of these questions and their prospective answers. Though since the topic at hand is terribly broad, let us begin with one aspect—the dire poetic environment we inhabit—that we might start to gain a foothold for our ascent.

Useless and Ugly Poetics

If we are to ask “What are we to do with Poetry?” and specifically “What of Poetry for the Posterity?” we ought to take full consideration of the circumstances. Poetry is in a sore state. Perhaps worse now than when it was degraded in the past. Today, our challenges are daunting. Some of them are the consequence of technology and some are the result of human motivation—ideological and otherwise. Among the most devastating has been a pincer maneuver that assaults discriminating taste while simultaneously deploying limitless assimilation4. It must be fully realized that a precious bastion of humanity is under attack. If we wish for Poetry to thrive, it is time to launch a counter-offensive.

Let us then state clearly the circumstances that the reader and the poet find themselves in. The celebrated poetry of our day is stupid, asinine, humiliating, sterile, laborious, ugly, treacherous, posturing, insulting, worthless, destructive, licentious, false and an all around affront to decency and greatness. And when it is not busy being a grotesque monstrosity, it addresses us as naked propaganda, not even having the courtesy of making itself comely. If poetry is to be propaganda, at least allow me the swell of passion in my breast, but no such pleasantry is afforded. Apparently, I’m not only to be molested by a whore, but an unsightly whore5 at that. Whatever happened to dignity? Shredded. Along with the rest of our attractive poetry.

The language of beauty no longer fills tomes illuminated by scribes but is recorded by accountants in ledgers. Aesthetics no longer concerns itself with moving the soul; It’s busy moving the dial. It’s got to do numbers, impressions, click-thru’s, views, likes, shares—you know the drill. On the other side of the equation is poetry that’s a big nothingburger; Two big soggy buns and no meat. Those poems should stay in the writer’s diary. If they don’t, you end up reading about the glorification of tomato-eating hedgehogs6. Which Muse does one invoke to write inanely about hedgehogs? Alright, that’s enough bloviating complaints. Grievances sufficiently enumerated, let us pursue something more constructive.

Poetry, the Poet & the Problem

Poetry is seen as effete, pompous, and onanistic. In light of recent poems and the usual, commensurate insufferability of poets, this judgment is not without standing. The poet is therefore tasked with proving otherwise. He’s going to have to show a little nerve—this dog still bites. Why do our poets insist on indulging insignificant matters of mundanity? Poetry has always attended to matters of importance. Why settle for such pittance any longer? Not every poem is an epic nor should it be, but I believe we should clamor for more than “Today I Was Sad: The Poem.”

Poetry’s got guts. It’s time we act like it. Neither is Poetry a triviality. It has real importance. It means something. I hope that elaboration of the meaning crisis is no longer necessary. Every man who’s got his wits about him should’ve intuited that meaning in our lives is an increasing rarity. A poem, for a moment in time, is a substantiated monument of meaning. Why pretend that a poem is a superfluous amusement when it is in fact a lightning rod for the heights of human expression. It is a travesty to treat poetry with such cavalier ignorance. A queen is not treated as a bar wench (This of course is no reflection on how one treats bar wenches.) Queenship is an overstatement of Poetry’s rank, but regardless, we could at least show a bit of propriety.

Returning to the poetic circumstance at present, let us briefly consider the reader. The situation of the reader is at once immediate and forthright: He doesn’t know how to read. If it’s one thing that modern schooling excels at, it’s teaching the student reading without learning how to read. To be accurate, the student is allowed no interpretive lens by which to understand, which is to say prejudice. The student is allowed no prejudice7 to judge what he has read. He is taught to be a computer—word processing as opposed to understanding.

The educational procedure instills catastrophic self-conscious subjectivity. This procedure requires the student to understand himself as subject and self-consciously insert the self between his mind and what he is reading. There is no longer the knower and the knowable, but now the knower, the self, and the knowable. And in fact, when the transmutation reaches completion, what remains extant is the self and the knowable. The reader no longer understands himself as a knower. In digital terms, he is an algorithm, not a knower; he is hard-wired, not inspired. The knowable is data, the self is code. The self seeks programming, preferably self-programming, though now, increasingly he is in search of a programmer.

Paradoxically, the radical application of the self-conscious self destroys the ability to recognize the human person and the soul. This is why the poet no longer sings and lacks the confidence to sing. The confidence in the soul and the confidence in inspiration are the preconditions to actualize a poetic expression. A soul is necessary for man to be a receptive being, and so now, with doubt (or ignorance) of the soul, there is no possibility of truly transcendent reception. The poet no longer thinks of singing or about the object of which he sings. The poet thinks only of the poet, and since the poet does not sing, the reader does not hear, and so the reader can think only of himself. At the end, there are only selves thinking about selves—speaking about selves8. In this state, poetry becomes an exercise in diminishing returns and the concomitant, fatal lack of interest.

None of these obstacles are insurmountable. Good poetry is interesting—it’s engaging. It will fascinate the reader, provided he’s been taught to hear the music. Which returns us to our current challenging tasks. On the poet’s part, he must not only write good poems, but also write poems that teach how to read poetry. This is exceptionally difficult and the poet must be humble, as his desire to be great may throw his instructive project into jeopardy. A book written to help a kindergartener learn to read will almost certainly never achieve greatness. Paradise Lost is great, Goodnight Moon is not, but who can despise the latter? Both have their place9.

As for the reader, he must be hungry. He must refine his palette to desire finer foods. He must desire more out of his poems. He must go at them like Torquemada, ruthlessly questioning until they confess their secrets. The reader must be confident that there are treasures to find in poetry and he must become indignant when he digs up fool’s gold. A poem is a microcosm of adventure, discovery and elation. “Microcosm” is perhaps the heart of my poetics. Poetry reflects the Cosmos inside itself. That is no small thing, and the reader ought to embark for himself.

There are three kinds of reader: one who enjoys without making a judgment, a third who judges without enjoyment, and, in the middle, one who judges while enjoying and enjoys while judging. This middle one reproduces a work of art anew.

-Goethe

II: Circumstance Considered - A Deeper Assessment

Talkative, anxious, Man can picture the Absent And the Non-Existent. - W.H. Auden, “Progress?”

Poetry: The Massage of Annihilation

Current poetic taste is enraptured by annihilation10, that is, the lust of Nothing—of non-existence. However, since annihilation is beyond mortal control, a surrogate form must be pursued. Immolation, flagellation and vivisection are frequent substitutes. I mean this metaphorically, as symbolic exercises11 in symbolic space, though materialization of these conjurations is not uncommon. Specifically, one of the main targets for destruction is the self. As we have seen, the self12 has become a burden on the soul of man. If the self can become scapegoat, the human can become free. The introduction of the radical self formulates salvation through annihilation—nothing can be saved, therefore everything must be destroyed. Having defeated the necessity of choice, the self pines for freedom from being free. At the end of things, the intra-historical hope of mankind is that annihilation will destroy death.

The self seems to be hunting for total disintegration. Through unconstrained freedom—that is licentiousness, the abuse of freedom—the self seeks to fundamentally dismantle categories or the ability to distinguish. This attitude continually appears in the workaday poetry of our time. I believe this is a concerning development. On the surface, annihilation expresses itself through total lack of concern for form. This includes conventional form, logical form and even grammatical form. In rejecting grammatical form, poetry can express non-sense, properly speaking. Poetry is being used as a vehicle to indulge in the utmost amount of non-sense tolerable by the human being.

If you go to the bookstore and pick up a volume of contemporary poetry, you may notice the astounding amount of white space on the page. That open space is reflective of the taste for annihilation. The empty space represents limitless possibility. The perfect expression of contemporary taste would be the totally blank book. The blank volume of poetry could succeed in freeing poetry from being poetry. The first edition would merely state “Poetry” on its cover, and the second edition would do away with a title completely. The dialectic that produces the blank book is the postulate that absence defines presence. It’s not essence that distinguishes existence; Instead, existence is given validity only by reference to nothingness.

The Annihilative Project Protects Itself

Now, these are ideological positions, and these positions can express themselves politically, socially and aesthetically. Also, as it is tantamount, they express themselves poetically. The translation of ideology into poetry is an example of the production of motivation. By motivation, I mean to suggest that annihilative poetry is an expression of human nature or desire. It is a special type of motivation and it is unlike other rudimentary, immediate motivations such as the ones that forcefully influence politics (food and shelter, for example.) However, since it is indeed a motivation, it can be deliberated about (that is, to be questioned and decided about) and in the poetic context, to be criticized. As opposed to the “natural course of History” the deliberative-critical question is: What is the best thing to be done?

Within the activity of deliberation, motivations will emerge that are contrary to one another. The conflict of motivations conceives necessity; And necessity13 is a harbinger for the crimson horse of war. To consider Poetry is to consider the human soul. To consider Poetry and Posterity is to consider History, which is to say motivation and circumstance. (This History is one of deliberation and choice; Not the “History” of pre-determined political progress.) Therefore an adequate examination of Poetry and Posterity ought to exhibit a sensitivity not only to the soul, but to the motivations that drive human action and to the circumstances which allow and restrict the substantiations of motivation. When circumstance that is caused by one motivation restricts the necessary substantiation of another motivation, war14 results.

The admission of war and death into human activity is absolutely intolerable to a certain predisposition of mind. Specifically, a mind which holds ideological positions that seek annihilation and one which finds purchase in contemporary poetry. It is intolerable because the admission of death, particularly the permanence of death, demands consideration of the transcendent. Transcendence, rightly understood, is beyond the powers of will and consequentially implores submission. The ontological impingement of the will is unacceptable. Therefore, a great sabotage of human deliberation must be undertaken to prevent consideration of human activity, motivation, soul, nature, and death. For if we begin to deliberate on death, we may deliberate on life, and also on Poetry.

The ideology of annihilative poetry must avoid becoming a motivation. If the truth comes out that the annihilative project is a motivation like any other, it can be deliberated about or criticized. The current poetic zeitgeist does whatever it can to function as a meta-motivation that exists above criticism. The contemporary poetic project is an occult one. The true core is hidden while criticism attacks its proxies. The project does this in order to prevent a war over its domination of poetic practice.

A Hell-Sprung Liturgy

It should be noted, at this juncture, that literature as religion15 has already been tried and found wanting. Though of course it still has its adherents and attempted revivals. However, of much greater importance is that poetry, at present, is serving as liturgy for the religion of humanity. In and of itself, this liturgy is incredibly fragile since deliberation is a constant threat to its survival and success. How then, does one protect this liturgy? Through the production of façade, counterfeit and falsity. Nevertheless, a deeper truth needs to be revealed. The liturgy’s fragility is in fact its strength. As I said, this liturgy requires protection in the form of counterfeit production, but what is occurring is the production of counterfeits to hide other counterfeits. Poetry-as-liturgy of the religion of humanity is in fact, façade. Alternatively, stated in the offensive mode, as opposed to defensive, it serves as a decoy.

The purpose of poetry is no longer to make poetry, it is to produce the façade poem. The façade poem, or dummy poem, distracts from true weakness and attracts genuine, offensive energy which the dummy poem transmutes into ineffectual, surrogate action. Just as a pretender king obscures and mediates true power, the dummy poem provides pretend authority. This is how human deliberation is sabotaged. By encouraging surrogate deliberation about pretend power, the religion of humanity ensures its own safety; Because human activity which could cause mortal wounds16 is absorbed by the dummy power, or in this case the dummy poem. We can criticize contemporary poetry all we want, however we shall never win any ground because we are effectively attacking a stuffed shirt.

It is not surprising that poetry17 is a premier weapon in defense of the dogma of the religion of humanity. It is mechanically sound. Within the framework of annihilation, the soul is referenced by its relationship with nothingness. The soul is real because nothingness is more real. However, since this predicament is increasingly destructive to the human being, poetry is required to provide the massage. The flexible and lubricative qualities of poetic expression allow the smooth operation of ruinous apparatus. When warfare is pushed into the symbolic, poetry becomes a potent munition.

As a literary form, poetry is incredibly exhaustive of language itself. This means that poetry is an excellent focal point for the production and domination of non-sense. On one hand, poetry can apply itself to the crafty production of non-sense; While on the other, poetry being used for non-sense shuts out the possibility of poetry expressing exhaustive meaning. A triumph of a deadly scenario.

Revenge of the Mirror

It is indeed possible for a human to be “sick” and desire things he does not want. People are capable of saying “This will not make me happy, but I’m going to do it anyway.” It is like worshiping a false idol which one knows to be false. Sometimes the false worship is pleasurable, and the worshiper is unwilling to give it up. Sometimes the worship is beneficial, and the worshiper will not give up the gains. Sometimes the worshiper is too afraid to cease worshiping. There are many reasons a man falsely worships a false god.

The false god of annihilation seems to offer many gains, and it absolves a great deal of personal moral responsibility. However, as is my recurrent theme, annihilation morality retains the façade of true morality, often bringing consent-based morality to critical judgments. A poem cannot be judged or justified because the poet’s intention—mere intention—determines the critical worth of the poem.

This predicament is untenable, however. The Deliberative-Critical Question is an irrepressible force. The mirror shall have its revenge; Though previously shattered by dissolution, the shards nevertheless reflect. The poem as avatar of the poet can only go so far. It abandons both the text and the reader. Current poetic taste survives on the “god behind the god” occult nature of its true source, but at the expense of genuine poetry languishing on the margins. Which just so happens to allow us to talk about poetry once again.

Our purpose when considering Poetry is to leave it better than when we received it. At least that is our intention and hope. The purpose of part II has been to begin to develop the ability to distinguish the genuine from the counterfeit; And to recognize the concomitant conditions when engaging with the counterfeit. Deliberating about the counterfeit18 is a precarious enterprise. The danger of slipping into surrogate activity is ever present. That is precisely what I wish to avoid.

yes, it well could be that my Flesh

is praying for “Him” to die,

so setting Her free to become

irresponsible Matter.

-W.H. Auden, “No, Plato, No”III: Failure and Sabotage of the Permanent Things

Precepts Good Precepts we must firmly hold By daily Learning we wax old. -Robert Herrick

Tradition Interrupted

The taste for annihilation has wrought an immense and subversive project which has helped interrupt the handing down of the Permanent Things. Now, a question: Why has the substantiation of the Permanent Things failed? First, I take it as given that the Permanent Things are not a real part of our contemporary culture. To be clear, the permanent things are, approximately, the content of Tradition.

When we hand on Tradition, the permanent things are the individual things we teach, along with the very concept of permanence (I.e. Human Nature.) Our culture does not care for Tradition. Despite the limp-wristed protests, we prefer innovation, efficiency, technology and power. Why then, even after a century of warnings, prophecies and lamentations, have the permanent things continued to lose significant ground? Honestly, the question may not have a full answer. There may very well be some mystery at play.

Let us examine a few basics. Tradition can not be preserved, conserved or kept. It must be continually renewed. Each generation must re-learn the permanent things, that they be re-ignited within themselves. Every traditionalist will readily admit this; And so we have our basic conundrum. Permanent things won’t be canned up in jars like ripe peaches or suspended in formaldehyde as an odd specimen. Year after year, we must cultivate them on the vine. This is the reality of the task. It’s laborious and prone to innumerable ways of failure. Just as a crop will be consumed by locusts, struck with disease or starved of nutrition; So do the permanent things succumb to devourment, pathology and wasting. This will suffice to chart the ley lines of our pursuit.

An initial fault may lie within the traditionalist himself. He may begin to romanticize the ruins; Another basic conundrum. With tragic paradox, he may, out of a desire to perpetuate the greatness of the past, fall to worshiping the past—that is, worshiping something which has died. Ruins may have an allure to them, but no man builds in hopes that one day his buildings will crumble. Ruins are beautiful to the visitor, but tragic to the architect.

Only broken kings sit on broken thrones. When the traditionalist worships the past, he readily accepts the hardships of his labor. No one cares about his efforts and his work may be pointless, but he carries on anyway. He bears the burden upon his shoulders; An Atlas that stands athwart history, upholding the colossal weight of humanity with the strength of his ever further slouching back. Sadly, he does this with smug pride; Truly a man against the world. A striking figure cutting a silhouette against the dying of the light.

I will refrain from showing in detail how this failing traditionalism manifests in poetry, as the reader will make the connections without much difficulty. In brief, new poetry is bad, simply because it is not old; And because the poems a traditionalist cares about go unappreciated, he returns the favor with unappreciation of his own. A brief example is the case of the Formalist. The Formalist does not appreciate, even though good form makes good verse, it does not make good poetry. The mysterious core of poetry precedes form and does not find its source in form.

Let’s move on to the extremes of the traditionalist perspective: The Pessimist and the Optimist. The former overstates our current challenges; The latter understates. It will be adequate to say that the Pessimist believes that poetry does not exist and can not exist; And so, all we can do is read old verse, and that’s that. Some fundamental transformation of reality has occurred that has rendered poetry unviable. Whether it be an essential change in nature or perhaps that the linear course of History has left poetry behind, poetry is impossible. Some consider this predicament to be permanent and others take a softer line, that though impossible currently, times could change and reopen poetic possibilities.

The Optimist, on the other hand, does not give sufficient credence to the difficulties that the permanent things face. He believes the permanent things will take care of themselves—they won’t. He thinks the permanent things are self-evident—they’re not. He trusts that, in the marketplace of ideas, the permanent things will ultimately triumph and win the acclaim they deserve—good luck with that.

Ironically, both the Pessimist and Traditionalist suffer from inaction, each in their own manner. The difference between the Pessimist and the Optimist is that the first refuses to wage war while the second foolishly wages war. The issue with the latter is that the Optimist fights for symbolic victories because he fights on a simulated battlefield. Which brings us to sabotage—among the foremost reasons for traditionalist failure.

Tradition Sabotaged

Unwittingly and not, the permanent things have been sabotaged. The promulgators of the permanent things, its very defenders, have often destroyed traditional success. Almost always because the traditionalist desires to be respected and accepted by his enemies. The traditionalist wants to be seen as beneficial to the establishment. Not to mention that he will be rewarded for serving as token opposition to the establishment. The token traditionalist wants to be nice, he just wants everyone to get along. It’s a sheer fantasy. He will be jammed down the barrel by the ramrod of progress and blasted out, aimed to destroy the very thing he wished to protect. The traditionalist—the conservative—does not appreciate the totalizing nature of our counterfeit system. Look at the movement towards formal poetry in the second half of the 20th century. It was all pointless and produced godawful verse. The reintroduction of form into poesy was flatulent, flaccid and unfulfilling.

Why didn’t the form help? Because the problem is in the poet, not the poem. Mere form is not very constructive, it’s only appearance—façade. The conservative seems to think that a skeleton needs no heart, that a vein needs no blood. And so, tradition has been championed by pinheads, imbeciles and traitors. They have, to tradition’s deterioration, pridefully chosen self-appointed bullshit principles over the prudential well-being of the permanent things.

Finally, the figureheads19 of this movement have continually been shown, upon enough introspection, to have been saboteurs. If we examine basic motivations, the reasons for sabotage are clear. The leaders of truly counter-cultural movements are rewarded for failure. Their purpose is containment, not success. In the public eye, everyone needs a boogeyman who’s worse than them. That is the purpose of tradition; Counterfeit tradition to serve as a counterfeit boogeyman in a simulated war over symbolic goals. A seemingly perfect system.

These are hard things but they must be confronted. Traditional movements can no longer afford to be duped by exploitation and sabotage. Traditionalists must come to their senses by recognizing their own interests. They must stop fighting against their own welfare for the sake of appearing principled. Unfortunately, what conservative taste fails to fully grasp is that the purpose of our culture is to produce sublimated suicide. Negotiation with our culture is negotiation with surrogate suicide20. The conservative naturally desires to operate within the rules of the game. However, he has not yet realized that the game is won by killing yourself. That is the horrific truth of our current tectonic cultural motivations. In the face of this, we must remember: Principles are not suicide pacts, Poetry is not a suicide pact. The traditionalist needs to identify and affirm his own motivations, if he is to survive.

Tradition Resumed?

An opportunity is presented before us. How well defended has the establishment left poetry? Are there weaknesses to be exploited? Perhaps. There are three permanent things which promise the possibility of transcendence. They are Eros, Death and Poetry. Despite the world’s commodification, massification and falsification, those three things remain. We Love, We Die, We Sing. The human being yearns to be more fully human. These three permanent things continue to offer a chance at self-actualization. We must ask ourselves if these are unguarded castles in the establishment’s counterfeit simulation.

Beyond delusion, man’s power has hard limits. Man’s power has not been able to enter the porticoes of poetry. Poetry’s walls stay standing, a protective garment of something more precious—sacred even. There still exists, in the white spaces of poems, a point where a man perceives his heart as a man. He knows for a moment that he lives. Just as when he narrowly escapes his death or becomes enraptured by beauty, he is overcome by the weight of existence. He knows, in that moment, that he is a man and that he lives; And that it means something. In the stillness, he knows there are miles to go before he sleeps.

Despite the flogging of traditionalists that I gave above, the fight has not been in vain. And I am grateful for the effort. The anger displayed above is, first and foremost, anger with myself; Anger at having been a fool. Also, anger towards what I believe to have been betrayal. Every man who gave the appearance of championing some part of tradition, but then turned around to purge his fellows in arms, has inflamed my ire. Additionally I have in mind men who have carried the legacy of past traditionalists, but then subverted them by sanitizing or belittling their beliefs. Therefore let us remember the many good men who have labored to pass on the permanent things. I will not besmirch their work or memory. Whether it be a Chesterton, Eliot, Lewis, Tolkein, Williams, Pieper, Kirk, Brooks, Adler, Lawler or Schall, I’ll remember them21. I’ll remember what they taught me. However, today we have our own challenges and those men have all gone. We can’t waste the gifts they’ve given us. We can’t indulge our egos and we can’t afford to be fooled any longer. Be wise as serpents, innocent as doves.

The Posterity must be protected. They must know what they’re up against. They need categories of thought which will solidify and defend them—a type of memetic aikido22. The spells of poetry as propaganda as mass ritual as politico-psycho-spiritual-suicidal-necrosis must be broken. The greatest thing we can do for them is give them confidence in their soul—the confidence to sing. We should continue to introduce them to the men listed above; And not only them, but also to Wyatt, Spenser, Donne, Milton and Dryden. It must be remembered, however, that we live now. No man should live in a simulated past, and no man should kill the present that the past may live. We must have vigor, passion and vitality. We must be up for the fight. So often, the traditional man has balked at poetic coercion because propaganda has pushed him back. I say, no more. As Mars, So Mercury23.

IV: Poetry and Leviathan

there on the waves a headless Emperor walked coped in a foul indecent crimson; octopods round him stretched giant tentacles and crawled heavily on the slimy surface of the tangled sea, goggling with lidless eyes at the coast of the Empire. -Prelude, Charles Williams

Poetic Nemesis

If the spell of the politico-psycho-spiritual-suicidal-necrosis must be broken, then let us open up the grimoire and have a look at the incantation. The psychic necrosis of modern man is that he is always on the cusp of becoming. All human activity suffers suspension in the Great Becoming. He is a paramecium in the megalithic vat of primordial potential. He is the great teeming mass, possessing only the infinitude of possibility. The Becoming is beyond comprehension, and man has no understanding of what it would mean if he actually became.

Therefore, the Great Exception has been declared. All action must end. All contemplation must cease. The entirety of humanity’s energy is required to focus the Becoming. Mass neuronal fusion of uncategorical capability and discrete cognition will manifest the heterogenous Beyond-Man24. Modern man lives on the knife’s edge of his own abolition. There are those who worship abolition and there are those who despair of it25.

This predicament becomes Poetic Nemesis26 because the goal of the Great Becoming is the elimination of the need for transcendence. It is a fundamental subversion of our natures which inverts the natural outward facing attention of the searching human gaze inward. There is no need to search for the transcendent when the immediate world satisfies us completely. At least that is the gambit—the complete simulation of the Infinite and Eternity.

Poetry’s Service for the Cosmic Hierarchy

When a man is born, he is admitted into the spiritual bodies which the world of his times patronizes or negotiates with. Organizational bodies govern and mediate all manner of human life across the various levels of being. Bodies of blood, of country, of cult, of physicality, and of spirituality, all serve to bind the life of men. These bodies are perhaps capable of harmonization in a sufficiently governed cosmological model. The well-governed model of all bodies seems to continually recur as the vision of corporal hierarchy. The corporal hierarchy, as conceived by individual men, seems contingent on the understanding of and the relationship to the corpus mysticum27.

The manner in which men live according to the mystic body appears to have incalculable influence over cognition, developing into both acceptance and denial, of the corporal hierarchy28. In the effort to negate traditional corporal hierarchy, the Everlasting Man is shunted into suspended simulation and the Abolitionary Man29 emerges as a doppelganger in competition for the governance and mediation of all bodies. Today, in our time, we are born admitted into occult bodies—that is, hidden bodies—as fairly advanced acolytes. The Abolitionary Man mediates unknown power from an unknown place for an unknown purpose. The rule of Abolition cuts across all bodies with a venomous “negation-of-exclusion” so as to poison the rule of Faith.

The role of Poetry in our eternal cosmic enterprise is multifaceted. Poetry is a record of action, is both an end and beginning of contemplation, and importantly, provides translational typology30 for the corporal hierarchy. Translational typology must navigate the symbolic transference31 which occurs across the bodies of existence so that men may be endowed with a cohesive and meaning-laden cosmology. It is therefore important that Poetry be simulated and subsumed into the occult bodies lest men begin to actualize Poetry’s true purpose.

We can see, across multiple levels, the domain of poetry; And why it is threatening to the project of the Great Becoming. Poetry utilizes both Logos and Beauty. It transcribes action and inspires action. It provokes contemplation and expresses contemplation. Poetry is both Word and Voice. In its higher modes, it blossoms as both Contemplative Praise and Divine Mania32; Each being a phenomenon which is incomprehensible to Abolition33.

Finally, in poetry we can find the reconciled man, as in the Psalms. The reconciliation of being is detestable to the spirit of the world because reconciliation is anti-becoming. All creation groans not to Become, but to commune with what Is.

Lust of the Flesh & Lust of the Eyes

The spirit of the world aims to negate reconciliation via the establishment of an imposter—the Amalgam34. Through proliferation of the systemic androgyne35, the Amalgam is at work to disperse the perception of ontological category. Its ultimate end being the fabrication of a fully collapsible36 system which is capable of the radical flattening of perception into nothingness. This system must be rid of contemplation by first collapsing contemplation into action thus creating hyper-action. Which then allows contemplation to be simulated by use of non-referential signs. The forms or patterns of hyper-action are translated and transmuted via acephalous typology37 into counterfeit contemplation, thus thinking is always acting as there is no escape from the counterfeit pure act. Finally action is simulated, by and within temporal authority, so that no single act can push the actor into contemplation. At this point the transformation of contemplation into hyper-contemplation has occurred since hyper-contemplation is merely abstracted hyper-action. Inside the walls of this cauldron the Amalgam simmers, accruing mass—this is the creation of the giant flesh. All the while, excess nutrition builds without actual expenditure.

The spirit of the world seems to be birthing in its subjects the lust of the giant flesh—the pathological drive to increase. Incessant stimulation, apart from interrupting contemplation, serves to grow the occult body. This appears, on the individual level, as indulging in non-teleological stimulation. Thus, human activity becomes more and more prophylactic as it continues to separate stimulation from result. (Possibly, this is reflective of a desire to separate Sin and Death.) We can see the physical status of the great becoming in the production of the giant flesh. The human being is suspended in the flow of always growing—always becoming.

However, as is learned in myth, those who build the giant flesh—the Giants—need to avoid the wrath of Zeus. Therefore a project of disincarnation must then be pursued and the stratagem of the disincarnation is that the flesh becomes word. Now, the growth of the physical giant flesh is concomitant with the growth of the psychic flesh, but importantly, the physical flesh is used to impose specific spiritual orientation onto the psychic flesh38. The flesh-made-word serves as the conduit to manifest the beyond-man, which is, perhaps, the illusory hope that man can exist outside the power of God.

A technique that the world uses to produce the giant flesh is the transmogrification of garment into flesh. All manner of garments of death can be absorbed into the flesh. Poetry, for instance, can be seen as a garment of flesh; And not just poetry, but many forms of word can be seen as such. The occult body is occupied with amalgamating garments into the giant flesh. However, this unnatural lusting after addition comes at the cost of sacrificing generation in favor of prophylaxis. Effectively, the manufacture of garments and their subsequent assimilation may be the desire to master death by becoming more akin to death.

At this juncture there appears to be a divide about the production of the Beyond-Man—the Beyond Man may not be possible39. Either beyond-man is achievable and therefore death is conquered or beyond-man is not viable and death can only be conquered by consent. The amassing of garments thus becomes surrogate suicide as human activity is ignorantly focused towards negotiating about the terms of death. The state of constant becoming leads to human exhaustion via depression. And so, the repetitive collection of garments is sought as the consolation of consent in suicidal suffocation40.

Poetry, Nakedness & Babylon

We must ask ourselves what role poetry can play in the circumcision of the giant flesh. To what degree can poetry cause the reduction of appetite? Through poetic circumcision41 and coercion, poetry can serve as an exclusionary king governing its domain. It can meet the Amalgam as the Sword. It can counter Mass with Form. It can approach Possibility with Virility—Fertility with Pregnancy; And therefore cause the cessation of Becoming with the beginning of Birth. The choice narrows before us as beyond-man or begotten-man.

And so, symbolic or typological categories must be increasingly reckoned with—White garments and black garments; Apparent death but actual life, or apparent life but actual death; Submission or Simulation; The revelation of Divinity or the deep things of satan. Those who choose the surrogacy of suicide, choose the darkness of simulation and gnaw on their own tongues of self-referential speech.

Now, what we have been discussing by the mention of garments and circumcision is, fundamentally, nakedness; And further, the mediation of nakedness. Even further, nakedness mediated by the spirit of the world—Leviathan, the one who twists, the great city Babylon.

Nakedness, being a permanent fixture of the earthly human condition, must always be dealt with or otherwise conceptualized. It must be considered in both the physical flesh and the psychic flesh—the body and the heart. What man is undergoing is the preparatory breakdown of his interior for the collapse of the exterior into himself. The patterns of the city are to be imploded into the individual after the natural patterns have been made void of Divine permeation42 via memetic aphasia43. The person no longer rightly perceives or discerns the correct nature of things.

As for nakedness, Babylon the Beast dictates the character of nakedness, in both permission and revocation, in ways such as shame, pride, pathology or egalitarianism. The exact manner of disposition greatly influences cosmological perception, especially in so far as the mediation of nakedness has been submerged into the spiritual. Therefore we must be diligently watchful for antichrist in the subtle things of the world. As the kings of the earth continually attempt to produce the common, the threat of Babel is always at hand and consequently the confusion of tongues. The tower looms, ready to collapse into the heart of men. For inside of them lies the potential of a Temple of Christ or a Tower of Babel.

Babylon awaits, patterning man after itself, in anticipation of entry. Slowly, the seduction of the subject into Whoredom is being massaged into assent. The volitionary lubrication from the defilement of innocence decreases reluctance and increases pleasure as drunkenness swells. The subject as Whore overcomes his conscience with the bloody consumption of innocence as Sense and Sanity are released from human grasp. The consideration of poetry in this context must recognize the abilities that poetry has in navigating the mediation of nakedness. It is, however, incapable of mediating nakedness itself. Placing poetry in the role of mediator is the same as erecting an idol. This, however, will be done since Babylon is to be given voice and Whoredom will happily oblige. The poet, then, must be conscious of the tool that he wields. Fire may shed light, but it burns all the same.

Finally, it is of utmost importance that everything I have said must be considered at the accurate degree to which it has been accomplished. Intention does not directly translate to result. The project of the great becoming has not been fully successful, only in part. Surrogacy and simulation must be measured on a spectrum, and the Great Becoming has failed to accomplish many of its goals. I feel that I have given insufficient attention to this fact. The apparent failure of this project, which I have been describing, has many wide-reaching ramifications, many of which have yet to take form. I do not know how far technology will allow us to continue the Great Becoming, it may be a ways yet, or it may already be over. My main concern in exploring this topic has been to begin perceiving the damage caused by the project of Beyond Man; And the role that poetry can play in mitigating and ameliorating this damage. I am not overly concerned with the Great Becoming succeeding. This is because I believe that transcendence is possible, indeed always possible. Reality is extant, intelligible and ascertainable; For that is my faith.

The Scope of Poetry

I would like to assert that the preceding contextualization which I have engaged in, is necessary for the consideration of Poetry and Posterity. Also, I posit that the foregoing matters are befitting the discussion of Poetry. Determining the proper role of Poetry is a valuable enterprise and it must be looked at in the light of many other aspects of existence. Just as the philosopher has always pondered politics, culture, language, nature and indeed all things; The poet has done the same. This is because both philosopher and poet are concerned with the same thing: Wonder. Poetry, as an activity, performs sundry and diverse functions. It is a vessel for revelation. It records and defines a people. It stewards language. It navigates typology and symbol. It expresses hate and proclaims love. It is a permanent and edifying human activity. Therefore, it is to our own detriment if we ignorantly narrow our sights when we contemplate poetry.

And finally, in consideration of poetry—specifically of poems—we will have discovered that it is we who are the Posterity. Who else did Milton write for? Or Shakespeare? Or Wordsworth? They included us in their audience. We are the Posterity. We are the inheritors of beautiful things. We are the receivers of exceptional gifts. What remains other than accepting them? Beyond that, we work to pass them on; And not to merely hand them down, but to hand them down well. For it is not enough for man to simply live; He must live well44.

The men of the East may spell the stars, And times and triumphs mark, But the men signed of the cross of Christ, Go gaily into the dark. -G.K. Chesterton, Ballad of the White Horse

V: The Practice of Poetry

Towards the Enjoyment of Poems

Up to this point, I have excoriated failure and lamented destruction. Now, however, I would like to turn towards convalescence. Poetry really is a wonderful thing. It’s easy to indulge in agonizing over its demise. When the beloved’s face is marred, one naturally worries about the scar, and it is needless to mention the censorious wrath incurred by her mistreatment. The defacement of beauty is not merely an abomination but an injustice. I hope, then, that my indulgences have been understandable. What remains before us now is much harder work than pontification or theoretical analysis. We are left to the Practice of Poetry.

Fortunately, that is where the true gold lies. It’s in the lines, mingled among the rhymes, captured by the syllabic heartbeat pumping the lifeblood of poesy. Which is precisely where we must begin. We start by giving ample attention to the lines which amuse, embolden, pacify and amaze us. The crucial words being “ample attention.” A poem, above all, requires the chance to spring alive. Which means you must give it your time and energy—that is, contemplation. It must be considered and weighed. It must be felt and known. A man who has only read a poem once has not truly read it. Familiarity may breed contempt, but it also begets affection. The reader must reproduce the poem within himself. It must come to birth. Allow me then, to be the midwife.

Our goal is to enjoy poetry. Academic exercises are good and useful, but let them be subordinate. The Academy should supply aid and shelter for poetry. It can even critique poetry, but it should never engender poetry’s destruction. Indeed, critical standards are important, as men should have appetites for good poems. A man should consume what is befitting him; Neither returning to vomit as a dog or counterwise, ingesting the flower of the lotophage. By which I mean, neither the poetry of detritus and disgust, nor self-gratification and saccharinity. However with that being said, a man ought enjoy the good just as much as he ought not reckon bad as good. Then with our eyes trained on the horizon of delight, let us, east of Eden, make our way.

Upon a Scarre in a Virgin’s Face

‘Tis Heresie in others: In your face

That Scarr’s no Schisme, but the sign of grace.

-Robert Herrick The Simple Pleasures of Poetry

Now, let’s begin at the beginning with a moment of reflection and appreciation for the simple pleasures of poetry. The first delights of poetry are essentially those of song. It’s the jingle-jangle of connecting euphonious words. It’s the rhythmic recurrence of up-and-down’s—like bouncing a child on one’s knee. It’s the “ring of the bell” each time a rhyme goes off. It is in the auditory medium, the physical medium, where we paint our first strokes. The most immediately gratifying beauties are captured in the ear.

Philosophically, the physical medium of poetry correlates to the fact that we are a physical being. The invisible word is made material by the act of the tongue. Pronunciation manifests the immaterial into physicality. It recruits the teeth, the palette, the throat and the breath to fashion an actual thing—like an ark pushing off and sailing through the air. We are not mere minds, we are bodies, and poetry is a premier medium to express that fundamental truth.

If we wish to study a pure subject that explores raw embodiment, we must focus our vision where poetry initially enters our lives—the nursery rhyme. The nursery rhyme is the first rung on the poetic ladder. Even if we wish to climb higher, we must always take the first step. Nursery rhyme is sheer practice, sheer word, sheer convention. There’s no title, no author and no pretense. It survives on tactile joy alone. And some of them carry hundreds of years of editing and refinement. We’ll start with a favorite of mine: The concluding couplet of “Oranges and Lemons”.

“Here comes a candle to light you to bed, And here comes a chopper to chop off your head!”

I’ve loved these two lines ever since the first time I read them. Encountering them first in text as opposed to song is strange, of course, but it wasn’t one of my nursery rhymes. It’s an English song and it only makes sense in England as it is about the various church bells around London. Here’s the line from which the title comes from:

“Oranges and Lemons, Say the bells of St. Clemens”

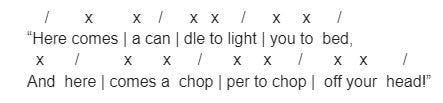

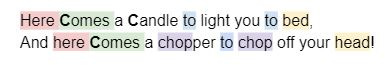

Now, the final couplet has always captivated me. In addition to being amusingly morbid (which happens to be to my taste) the lines have several characteristics which make it good, and which I would like to draw your attention towards. Here is a scansion, so that you can see how it is supposed to be read:

Also, this is basically how it is sung, you just have to add in the melody line. The slashes indicate where you place the accent, which is to say which syllables get more emphasis.

This couplet is almost hypnotic, and it’s certainly delightful. Initially, we can examine the logical organization. The first line is about going to bed and not only that, but having a candle so you can see where you’re going. It conveys peace, safety and rest. The second line achieves some breakneck irony as it is about being decapitated. The sharpness and severity of the reversal (the thrust-counterthrust) creates the effect which engages our attention. This irony could have multiple effects, but several prosodic features control the tone to achieve a comedic or amusing outcome.

The ironic juxtaposition of pleasing banality and sudden morbidity creates much of the effect. However we can see how the anapestic bounce of the meter helps craft the humorous tone. Also “chopper to chop” does a majority of the heavy lifting in this regard.

As for the hypnotic quality, observe the repetition in these lines:

Three hard “c” sounds, two here’s, three to’s, two chop’s and finally the rhymes. This repetition induces a spell-like fixation. You may find yourself randomly repeating these lines while you’re walking, doing dishes or taking a shower. Just like you might do with song lyrics. The heightening of repetition lends itself to a trance-like, attention grabbing conjuration of words. This poetic fundamental can be extended to larger patterns of repetition such as the stanza, or even buried in the sense units across long stretches of verse. Here we can observe it in an immediate and potent form.

I’d like to draw your attention to the fragility of this line. I would contend that the word “chopper” is necessary for the success of this couplet. Observe what happens when the word is changed:

Here comes a candle to light you to bed, And here comes a knife to chop off your head!

Even though the sense is maintained, “knife” spoils the line. For one, it drops a syllable, affecting the meter. It interrupts the anapestic gallop. Not necessarily a bad thing mind you, but in this case, a negative change. Secondly, it’s not funny. Observe what happens when both sense and meter are maintained:

Here comes a candle to light you to bed, And here comes a cleaver to chop off your head!

“Cleaver” keeps the sense and the meter, but the humor is still lost, as is the repetition of “chop.” Once again we’ve crafted an inferior line. When language is versified, it is heightened to a degree where words become very unique, to the point of irreplaceability. This feature of verse bestows words with a great deal of power and expressive ability. In competent hands, words begin to crack like thunder and blind like lightning. A good poet sharpens words to such a degree, that as the reader reads, he bleeds.

Alright, here’s another favorite of mine:

Hinx, Minx, the Old Witch winks, The fat begins to fry.

There’s something delightfully enchanting about this one. “Hinx, Minx” are like abracadabra words—talismans that can mean almost anything; And once again we have repetition. The meter is expertly controlled in this couplet. The first line has a relatively slow pace, which is then sped up by the second. The expectation set by the first line is opposed by the second, but it doesn’t break, and we’re left with a hypnotic little couplet.

What I’d like to show with this example is that despite the particulars which we have been discussing, there is indeed something that we can abstract. There’s a pattern here which we can take out of the couplet and approximate. Here’s my attempt:

Hip, Hop, the Fat Frog pops, The toads all jump in time.

It’s fairly close to a similar effect. At least it strikes me as having a formal similarity that “harmonizes” with the original. The first thing I’d like to note is what features have been abstracted and re-particularized in the new verse. The meter has been kept, and attempts at retaining the alliteration, rhetorical structure, sense order, and tone have been made.

Secondly, I’d like to compare and contrast the two couplets in order that we might examine the sundry complexities that make up a verse.

Hinx, Minx, the Old Witch winks, The fat begins to fry. Hip, Hop, the Fat Frog pops, The toads all jump in time.

Notice that I kept the “Hinx, Minx” structure with “Hip, Hop” however I dropped the rhyme in favor of rhetorical sense and alliteration. The alliteration of “Witch winks” was transferred to “Fat Frog.” “Fat” and “fry” were kept with the alliterative “toads” and “time.” “Begins” however was broken into two words with “all jump.” Additionally the logical structure was maintained in that the first line directly causes the second. However, despite how many features were kept, the two verses ultimately differ in tone and effect to no small degree.

I would like to drive home the fact that there are a great many little things going on, and precisely, that these little things serve to define the identity of these verses. All these little characteristics fashion the voice of poetry. Just in these short few lines of no great stature there are an abundance of complexities and shades of texture. Despite this cornucopia of particulars, we can still abstract a pattern from the verse, which means we can get a language out of it, and that this language allows convention and communication to emerge with the practice of poetry.

A few more for good measure:

Ring around the rosie, Pocket full of posies, Ashes Ashes, We all fall down!

This one survived into my own childhood. Written in perfect trochaic meter. Notice again the repetition and alliteration employed. Might I draw your attention to the game of this poem? When you sing, in unison, the final line, everyone is supposed to throw themselves to the ground. In this case, we do not merely embody the verse with our speech, but also we materialize it in a bodily act. It’s a very dramatic and visible connection between body and word—action and poesy.

The popular practice of simple prosodic pleasures continues even into the 20th Century:

I do not like them, Sam-I-am. I do not like Green eggs and ham.

The hypnos of repetition in practice. Notice the effect Seuss achieves by taking a syllable from the second line and placing in it the first. He’s manipulating our expectations by fiddling with the line break. This is not to mention the repetitious and hexing “Sam-I-am.” Almost devilish if I don't say so myself.

The point I wish to make with all this is to affirm the validity of the simple pleasures of poetry. I hope to have said a few words in favor of constructing basic pleasing sounds; And perhaps to have hinted at the transfixing power that these verses display. If one desires to say something, it behooves him to pay attention to how things are said. Also, as I think is apparent, these simple pleasures are not exactly so simple. Indeed, there are quite a few complexities at play. As I said before, we ought to give verse ample attention, and if we can attend to children’s rhymes, we can attend to more mature verses as well.

Poetic Pleasures in Practice

We can observe that the poetic pleasures of nursery rhymes continue into more serious verse. Take a gander at this:

Gascoigne’s Lullaby

And lullaby my wanton will;

Let reason's rule now reign thy thought;