Many things can be said about bad poetry. Many things can be said about current bad poetry. The first matter of importance is that poetry has always been bad and will continue to be bad. Badness, then, should not surprise us. Therefore, the object of our discussion should be to say something useful about badness at the present time.

A note of historical context before we continue. It is not unusual in the history of poetry that periods of greatness are followed by periods of decline. When a Great Poet appears, there will be imitators that follow after him. They will not be so great. Alternatively, after a peak of greatness occurs, a sense of demoralization can prevail. “What more is there to do?”

I believe that a certain amount of poetic greatness was achieved in the early 20th century. I have slowly come around to this position. My appreciation of Modernist poetry has increased, as has my sympathy for Modernist poets. Frankly, they did well under their circumstances. As Goethe said, “Every century has its grimace.” Taking this into account, along with other compounding factors, a poetic nadir is not unexpected.

Now, I do not wish that the reader come away thinking that no good poetry is being written. My issue has primarily been with the celebrated poetry of today and the concomitant poetic values. The fact is that a great deal of good poetry is still being written. I have read much of it on this website. The difficulty remains that poetry needs to be actualized. It has to be valued and attended to. On the whole, poetry is simply uncared-for, and the poetry which is chosen to be actualized is poor.

The other matter I would like to address is the lack of specific examples of bad poems in this essay1. The first reason is that this piece of writing has doubled in size from where it began2. Its original conception would have not allowed enough space to adequately examine examples. However, beyond the specific reasons local to this essay, I would like to mention a few general problems in this regard.

The initial problem is that of offending taste. The least effective mode of persuasion is to take a poem that someone likes and simply call it bad. A reasonable man expects that an argument should be attempted for why a poem is bad. Nothing can be said against this.

Worse than offending taste is offending the poet himself. If he writes in a similar manner to a poem which you claim is bad, obviously the poet will be disgruntled at your criticism. However, you may not apply the same criticisms to his poetry for a myriad of, perhaps not obvious, reasons.

The poems which you choose to deride should be chosen carefully and examined gingerly. Ideally it should be a poem which you yourself are sympathetic towards. Loving disappointment makes better criticism than tart acrimony, even if acrimony is more entertaining.

Ultimately criticism resides in the particular object and not in generalities. Generalizing or abstract criticism, which I am about to engage in, can be helpful and indeed clarifying, but it remains “loosey-goosey.” The resulting fluidity is salutary, and indeed necessary, even if finally insufficient. However, we only have so many words and so much time; We must make the most out of what we have, which means abstraction can be enormously useful.

That will serve well enough for context and clarification. Returning to the question at hand, I think that we can highlight three major flaws in the current practice of poetry. They are domination of content, total explicitness and clichéd privatism.

Form

The first problem is the domination of content over form. Form is either disregarded, derided or condemned to ornamentation alone. Form is seen as infringing on the ability of self-expression. In this light, form is intolerable because it is an artificial constraint on being “true to one’s self.” We have a priori prioritized personality as the quality of utmost value.

Two things can be said of this problem. The first is that a conflation of Rhetoric and Poetry may have occurred. (It is possible this is a defensive response to the sheer magnitude of propaganda.) A rhetorical expression, in the sense of sophistic persuasion, loses its power when its artifice is revealed. On the other hand, a poetic expression increases in power as its artifice is understood—our satisfaction increases as we better understand a poem.

It seems as if we can no longer tell the difference between rhetoric and poetry. As a consequence, our tolerance for artifice is incredibly low and the appreciation of poetry has diminished. We quickly begin to suspect that a writer is not being “real” with us, and disregard his expression.

The second thing that we can say about form is that there is a prevalent misunderstanding of form. Form has been poorly and incorrectly taught, often because it is considered too narrowly. Form is understood in its most contrived sense, almost in a mechanical fashion. It is as if the poet creates according to chemical formulas or as if form is a function box with an input, operation and output. Hence why the most artificial, fixed poetic forms, such as villanelles or sestinas, are emblematic of “Formal Poetry.”

In contrast to this foreshortened conception, Form, rightly understood, is the organizing principle of verse. It is not a set of rules3. Form is a complex dance emerging from the interplay of convention, communication and linguistic change.

Form and content do not snap together like Voltron and make a poem. The relation between form and content, and the poem is filial. Form and content beget a poem. The paternal form and maternal content intimately, inextricably join to create an offspring4. Two become one.

That is why activities such as paraphrasing a poem are unsatisfactory. Though we still can separate form and content as an abstract exercise, we are engaging in something akin to “This poem has its mother’s eyes and its father’s nose.” We are examining “genetic” traits which are simultaneously derivative and original.

Explicitness

The second flaw of current poetry is that the entire poetic expression is contained in its explicit meaning. Poems can be written completely on the surface and possess no implicit or interior meaning. The poem lays itself bare—no secrets, no seductions and no mystique. (Instead mystique is now primarily achieved via incomprehensibility.)

In the totality of explicit meaning, a poem paradoxically decreases in its ability to communicate. This is because a poem loses one of its methods of interplay. The explicit and implicit cannot play off one another. Irony, broadly defined as thrust-counterthrust, cannot be adequately achieved because an explicit poem often resolves as total thrust or total counterthrust.

(Irony here is being considered quite apart from “Ironic” and “Sincere,” both of which tend towards flat, explicit expressions. It is beyond the matter at hand, but I do not believe that you purge the poison of sardonic irony with the saccharine sweetness of sincerity. It is also a mistake to assume irony is “complex” and sincerity is “simple.”)

And to be clear Irony does not necessarily mean to undercut one’s own poem. You do not need to subvert in order to deepen or even give tension to a poetic expression. Implicit meaning is often an extension of the explicit meaning.

A poet plays with both denotation and connotation. One of the terrific features of poetry is that words do not to have be used with scientific precision. They can be ambiguous and unclear. Words, images and metaphors can be polysemous. Unfortunately, it is quite common to find poems that express one feeling and doggedly express that feeling along an unmannerly course without concerns of artifice or subtlety.

As a related aside, I might briefly discuss subtlety. It seems to me that subtlety is incredibly important, and perhaps necessary, in order to insulate tender or delicate things from abuse. “Somethings are too important to be talked about.” That is to say that certain topics or depths of feeling are better dealt with indirectly. Medicine becomes poison at a higher dose. A palliative meant to soothe may only serve to aggravate if it is applied too harshly or liberally.

To summarize, and make what I am saying more concrete, here is a test. If you can paraphrase a poem and feel as if little has been lost in the paraphrase, you are likely dealing with an explicit and shallow poem5. If a poem is merely chopped-up prose it is not making much of its poetic diction. We are looking for subtlety, aptness, depth or some such quality that makes poetry poetic.

Clichéd Privatism

If a poem leans too far into public meaning, it becomes cliché. If a poem leans too far towards private meaning, it becomes an obscurity. Frankly, little more needs to said. Poets seem not to acknowledge or care that a poem can be a public facing artifact. As with my previous arguments, I will once again assert that interplay has been lost—the interplay between public and private language. Poets would do well to take advantage of this dynamic in their poetry.

As for clichéd privatism, this is concomitant with the overvaluing of personality. If poetry is understood to be a method of sharing oneself with others, features of poetry which interfere with self-expression will be expunged. This is a type of poetry that desires to be seen not necessarily understood.

Ironically, the fact that private obscurity became so prevalent has made it cliché. A poem serving as an exhibition of personality becomes yet another expression which cannot be penetrated by the reader. It quickly becomes tiresome.

The other side of privatism is the expression of truly private matters. Often, when one bares one’s soul, the result is unfortunately embarrassing. Confessional literature seems to have more to do with therapy than poetry. I do not desire whatsoever to form critical opinions on private poems about grief, tragedy, self-abuse or the like.

The concept of subtlety once again surfaces here. It may be possible that through craft and subtlety both the poet and reader can achieve catharsis. The poet might still engage in a therapeutic act while also creating a legitimate public artifact.

Poetry, as I have been discussing it, is public poetry. I do not wish that my comments would be applied to private poetry. I take no issue with what individuals write in their diaries or share among their friends. My critiques are on Poetry as Art and they have no further purview.

Additionally, I do not wish my comments to discourage poets from writing poems. It is quite obvious that poets get better by writing more poems. A Criticism, which made in search of perfection, that prevents the further perfecting of the art is a poor Criticism. Don’t let the perfect become the enemy of the good, as they say.

All that really needs to be said in summary is that there is a difference between private-facing poetry and public-facing poetry. It is best not to publicly write private-facing poetry, or at least to not expect public-facing effects from private-facing poems.

Dynamics, Expression and the Poem

I might add here at the end, that privatism is the flaw that I am least concerned with. This is the flaw which is currently the most in flux. Privatism may very well be precipitating a re-structuring of homogeneous communication into a “regional” organization. That is, it is developing new “dialects” or local idioms in order to more closely bind people to one another. Or to put it another way, private language is attempting solve the problem of alienation by forming groups where the members can better understand each other. As a consequence, communication at large is growing increasingly difficult.

The flaw which I am more concerned with is that of Form and Self-expression. I think it would behoove us to understand that form can enhance expression as opposed to detracting from it. Form not only grants us a sensitive instrument for expression, but also increases intelligibility. Personally, I see an opportunity to extinguish the excesses of personality in the conciliation of Form. Perhaps I am alone in this sentiment and others will see it as absurd.

The contours of this essay have been along practical lines, more or less, and have eschewed “cultural” concerns. It goes without saying that cultural values greatly influence art and poetry. I would posit that our values do very few favors for the creation or reception of poetry6. However, we must use what we have at hand, which just so happens to be the poem; And so from the poem we can begin, and we begin by making better poems.

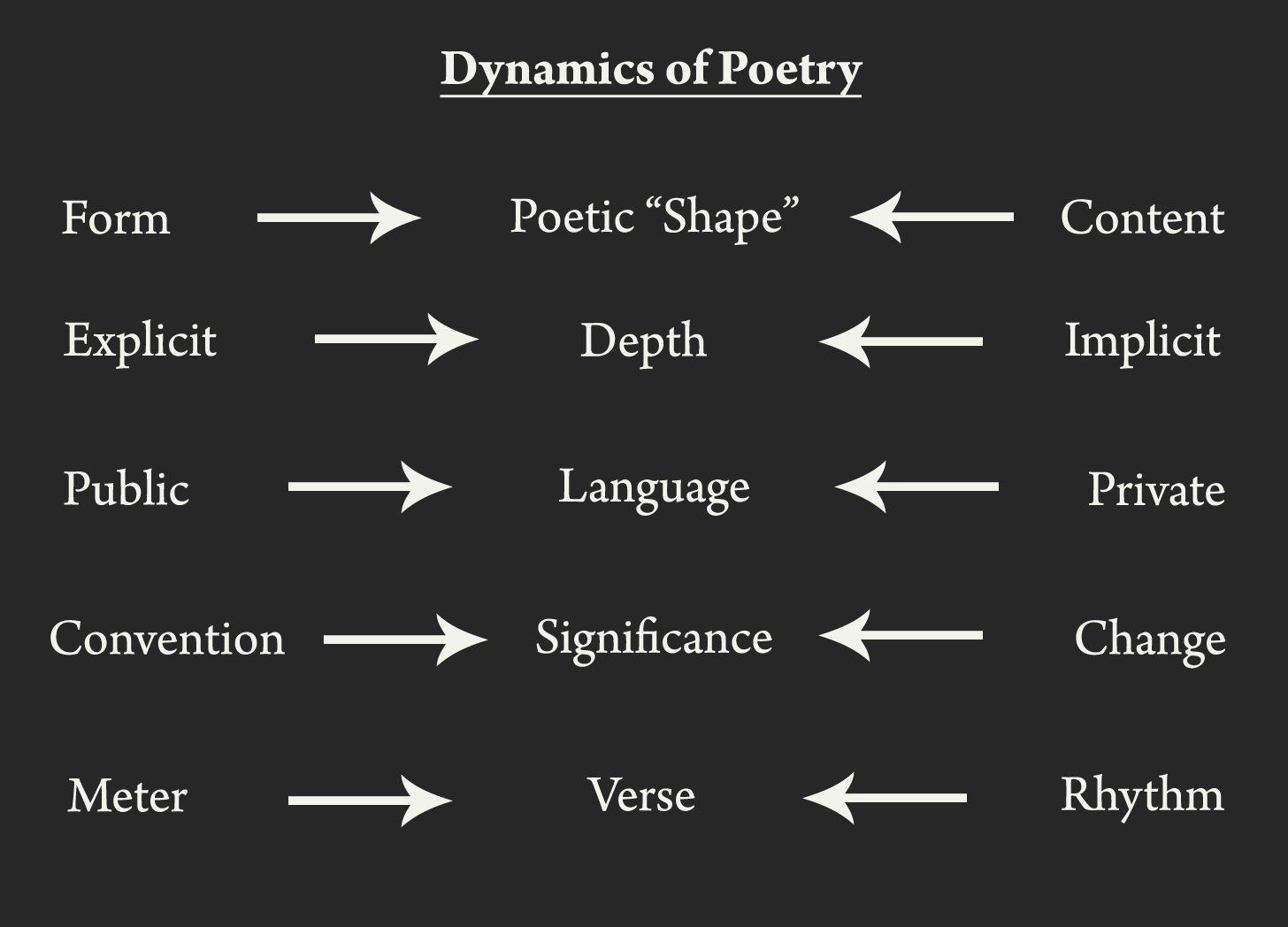

As can be seen from the course of my arguments, I believe that poetry is bettered by dynamism. My critiques follow the same line of thought—one side is dominating the other. Poetry is lacking form, implicit meaning, and public-facing language. The argument might be briefly extended to point out the prevalence of rhythm over meter and change over convention.

There are a thousand things that can go wrong with a poem. This has simply been an attempt to highlight major through-lines which may or may not apply as the case may be. In summation, my basic point is that the interplay of contrary principles is good for poetry. It allows greater expression, meaning and artistry to be achieved. It is rather unfortunate that we seem to have forgotten this. All in all, I can only hope I’ve given poets a few gobbets to chaw, and have encouraged them to pursue the fullness of their craft.

If the reader should wish, he could have a look at part V of my essay Poetry & Posterity, where I examine (and ridicule) a few poems:

https://acrossthespheres.substack.com/i/147295469/v-the-practice-of-poetry

This piece was originally meant to be posted as a Note, however I found it advantageous to expound on the initial conception. As it was meant as such, I ask the reader to forgive any undue terseness he may find.

We must admit that Form is indeed a set of rules. I am only trying to emphasize its organic and flexible qualities. Form is a set of rules, but the rules are supposed to be bent. Or stated differently, Form is a set of rules not a set of laws. They are rules to a game, not a moral code.

Masculine Form and Feminine Content could be written about at incredible length. The entirety of this essay takes place within the context of this essential problem—a discordant and rivalrous relationship between the masculine and feminine. It is damn near impossible to discuss this issue without falling into obscure discursion or wrathful polemic. You either go all the way around the mulberry bush and get nowhere, or lapse into anger and simply increase hostilities. The reader may conclude that the critiques made in this essay are intended to provide tools which may ameliorate this issue. Skillfulness in subtle and implicit expression may prove invaluable when dealing with woefully incomplete information or precarious scenarios, whether those scenarios be in romance or politics. Increasingly there is little daylight between those two areas. We seem to do our frigging at the ballot box, as it where. Politics is a terrible surrogate for restraining the monster, it seems to only increase its ferocity. The possibility remains that the monster might be better restrained in the sublimation of poetry—the area where things can simultaneously be said and not said. In the land of persona and semblance, a symbolic exchange may be yet be possible. I have no high pretensions for poetry; Grace alone heals Nature, but every church has its narthex—and its gargoyles.

This test is simply an illustrative exercise. I am not proposing that this paraphrase test can determine the value of any given poem. I merely intend to draw attention to the unique character of poetry qua poetry.

I engage in cultural criticism in Poetry & Posterity, particularly parts I & II:

https://acrossthespheres.substack.com/i/147295469/i-circumstance-considered-a-polemic

Great analysis, Nic. I appreciated your thoughts on form in particular.

If I could offer this: I think part of the problem is that there are, roughly, three poetry communities. Academic poetry (lit journals, university presses, etc.), popular poetry (Rupi Kaur, etc.), and everyone else. I would suggest that the first two groups haven't really been great stewards of the art form. I say that because it doesn't seem to me that they've done anything to increase popularity, interest or overall enthusiasm. In fact I'd say they've done a great job creating echo chambers.

That's why, bad poetry or not, I place my faith in that third group. After all, it's the oldest. It was around long before the publishing industry, capitalism or societies as we know them. Could be naive thinking, but it's my belief that if poetry has any hope of having a future, it's going to come from its oldest group of practitioners: no-name poets who inspired from the ground up.

I wonder how much bad poetry the great poets wrote compared to the ones that they thought publishable?

Perhaps the problem is the ease with which people today can publish whatever comes out of their "pen" without filter, so to speak...and so posterity will separate the wheat from the chaff?

Then there are those who reveled in doggerel...Kipling and Nash come to mind...

Lots of good stuff here, and some practical things to think about as I seek to improve my own poetry (even if I continue to revel in doggerel...😁).